Summary

In the northern part of Syros, in the village San Michael, there exists an ancient well bearing the name “Hellenico [Greek]”, exactly like the name of the place where it was found around the end of the 19thcentury.

The quality, the accuracy and the particular details of its construction, the exact orientation from South to North of the 27-meter access corridor carved in the rock, as well as a number of interesting observations related to the role of Syros through the years, led to an investigation by the National Technical University of Athens (NTUA). The results of this are summarized in this article.

Keywords: well, Hellenico, Syros, San Michael, watering systems, heliotrope

The work was funded by a private citizen who loves the island particularly, Mr. Constantine Georgopoulos.

Iosef Stephanou, professor and director of the Urban Planning Laboratory,was the principal investigator in charge of the work.

The following professors also participated in the investigation:

- Manolis Korres, professor of History of Architecture, Architect Archaeologist.

- Panagiotis Touliatos, professor of Construction, Architect with specialized knowledge in Ancient Technology.

The following complimented the research team:

- Julia Stephanou, Architect City Planner

- Samragda Petratou-Fragiadaki, Architect Eng, NTUA

- Michael Provelegios, Architect, Florence Polytechnic

- Vasilia Stephanou, Information Systems, Deree College

- Agisilaos Economou, Dr., NTUA Environmentalist, University of Aegean

The original text was translated to English by professor Constantine Hatziadoniu, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Southern Illinois University, USA, upon a request from the Cooperative of Ano Meria

Introduction

In August 2004, Louis Roussos, a taxi driver, an ex-sailor, a man dedicated with passion to the investigation of places and ancient references of the island of Syros, visited professor Stephanou at his house in Chalandriani, located upon the hill, in the north part of the island, in a place that he chose himself to oversee the archipelago and the Cyclades islands that surround Syros, right across from Delos.

The visitor tried, with an enthusiasm that distinguishes him, to convince the professor that a number of indications but also observations that himself had made assured him that the “Well Hellenico”, an ancient well that was discovered by villagers around the end of the 19thcentury, in the same-named location, in the village of San Michael, was not a simple watering well, but it was the famous Heliotrope of Pherecydes! Even though many of his observations (mainly on the site ) started from a wrong basis, since the ancient construction of the well included those parts that were constructed by the property owners after 1875 and, furthermore, the connection of history, legends and places in many points were relying nowhere but in his unrestraint imagination; however his enthusiasm and love for all these that he believed were such that one would only with difficulty decide to disappoint him or reject him. The same individual had approached many people not unrelated to archaeology and history, while he had managed to inspire enthusiasm and to motivate the interest about the Well of an exceptional man from Syros who, in spite the fact that his shipping business obliged him to live in London, he too fostered a great love for his birth place. This man had already accepted to fund the necessary Research (sic) which, even if it were not to confirm these theories, would, at least, shed light in an indeed remarkable, ancient monument of the island.

Moreover, there is a number of other data which always excited the scientific interest, such as:

- A number of archaeological sites [on the island] to a great degree unexplored, of which the remains, however, testify to a rich pre-history and history of the island.

- Some significant but not satisfactorily, until now, interpreted references of Homer to the island.

- The exceptional construction of this ancient well and the location of “Hellenico” in the village of San Michael, the northmost settlement on the island, on the side of the hill Panavlies (in the local idiom, payiavli=pipe, that is, the pipes of Pan or maybe the upper courts [avles=courts]).

- And, above all, the presence of the very important, even though long ignored, pre-Socratic philosopher, Pherecydes, whose personality and work often take mythical dimensions, and who was the teacher of Pythogoras, while in references of ancient writers appears as one of the seven philosophers of antiquity, to whom one way or the other he was a contemporary.

- The presence of two caves in the east side of Syros that both bare the name of Pherecydes and considered as residences of his. In effect, in one of them in the location of “Alithini”, near the same-named spring, there were certain ancient findings, like a marble bed, parts of a statue, parts of columns, etc, and a connection with an underground cave with a deep gulch at its edge and an opening at the roof.

- Finally, the mention of contemporary but also later historians in the works of Pherecydes and his heliotrope.

All the above combined with the privileged position of Syros with respect to Delos (only from Syros during each solstice one can see the sun rise from the island of Apollo, that is, see the birth of the God of the Sun in the first day of spring when he debouches from the sacred rock of Kynthos) made us wonder whether indeed the various remains of the past, material or not, natural elements, monuments, names, history, legends, traditions, etc, do not have secrets to reveal to us that we, until now, ignore. Maybe yet the revelation of these secrets could change the already shaped views of ours for many things that have to do with the very history of civilization, particularly of the western one, since this one in its totality has relied in the civilization that the spirit, the soul and the deeds of the ancient Greeks developed.

Already since 1995, when introducing the first International Conference for the Anthropology of space that NTUA along with the Association lnternationale de Ι’ Anthropologie de Ι’ espace had organized in Syros, professor Stephanou had expanded his theses on the exceptional location of the island across from Delos, which justified the interest of its ancient inhabitants for astronomical observations, but also the role of the Syros philosopher, who, from this island and with his work “Pentemychos”, led the passing of Greek thought from the analogical to the logical, from the one relying on the myth and analogy, to the one based, at last, on the proof by evidence, that is, the scientific thought.

Professor Korres’ Report

History of Architecture Professor, E. Korres, after taking into consideration all the evidence collected from an on-the-site study that lasted several days as well as from an in-depth examination of the monument, came up with the following assessment, interpretation and hypotheses regarding the construction, the purposes and the use of the well, all of which he provides in the following report from January, 2007.

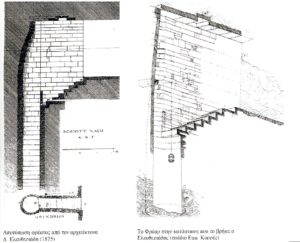

Forty meters to the right of the road to San Michael, Syros and just two hundred meters before the namesake church, in one of the graded levels of the sloppy ground facing north, where once the farmer stubbornly sowed and reaped, one finds an old well that, to a great surprise of the observant visitor, belongs to the most important monuments of the island: an ancient well with a characteristic lining of hewed stone. The location is called Hellenico, like so many locations in other places—those places where, according to a general rule of toponym derivation, there exist or have existed buildings recognized by the people as pre-Christian—. The ancient well, the most obvious, if not the only, ancient building in its area—and for that reason entitled to the name Hellenico—is already known to the experts. It was discovered in 1870 by the esteemed architect from Syros, D. Eleftheriades, who in October 1875, after removing the accumulated soil within it, he explored it and produced a drawing of it. His drawing that was published by L. PoIIak much later (1895) contains a lot of valuable information about the condition of the monument before 1875.

The present form of the building differs a lot from the original and it is questionable whether it would be possible to know the latter without an in-situ investigation. This became possible initially within the framework of a few-hour reconnaissance visit, on the 4thof January 2005, and other subsequent ones mainly in the time interval between 8-14 August 2007, all thanks to a related permission from the archaeological agency in charge. At this point, thanks should be given to Ms. M. Marthari, head of ΕΠΚΑ of the Culture Ministry for her support and to Mr. Louis Roussos, a knowledgeable resident of Syros, for his bold but fertile hypotheses about the heliotrope.

1. Ancient Water Supply

One can say, in reference to the ancient water supply works, that the principles of their operation do not differ very much from what applies even today. Main parts of their operation then were the extraction, transportation and distribution of water. From these, the second was often the most demanding one (long distances, water pipes, water tunnels, water bridges), while it was completely absent where the place of extraction and use were the same. There was also often a combination of a collecting pool and a fountain at places where a good aquifer layer met the surface of a ground slope. Again, in other situations, mainly when such a layer exhibited an opposite slope from that of the ground and there were seasonal fluctuations of water supply, it was necessary that the extraction work was in the form of a trench reaching to a depth enough to meet the lowest retreat level of the water during these periodic fluctuations of the supply. The drawing of water by directly dipping a vessel in it required accessing to its current level each time; this was done through inclined grades or steps. This ancient system, which is still in use in many places and is unique in waterworks of almost all categories (rectangular, circular or otherwise shaped open or covered storm pools, riparian waterworks from rivers or lakes of variable level, etc.) offers the simplest possible accessing, but it contributes more than any other system to water pollution. Besides that, when the steps are numerous, the drawing, due to the extra weight of the filled vessel, becomes very laborious. These disadvantages are avoided or rather constrained when the drawing and lifting of the water is made from above with a rope tied to a vessel. In Greece, the surviving ancient waterworks are innumerable, belonging to almost all categories and in all eras since the 3rd millennium BC and later. Most known examples of water accessing through underground corridors with numerous descending steps are, from the Mycenean times, those of Tiryns and Mycenae, while from the archaic and classical times those of Perachora. A special category comprises the wells with an access staircase within a perimeter corridor. But much more common were the wells with a mouth and pulley for the rope, such as those of Athens, some of them reaching up to thirty meters deep. The form of the ancient wells is of particular interest when two or more systems are connected through underground tunnels or when their space extends downwards for greater efficiency and storage capacity. Finally, there is a great deal of interest regarding their lining, whenever it is required, sometimes with prefabricated clay bricks arranged in successive rings and sometimes with normal masonry. Significant examples of the latter are the so called Kalliohron well in Elefsina or that of the sanctuary of Dionysus in Naxos, both late Archaic period.

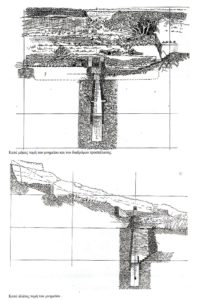

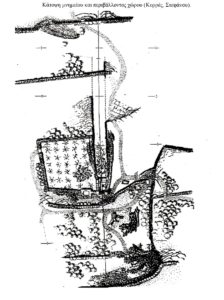

2. Well, corridor, road, wider configuration

Most of the common features of the ancient wells are also found in the Hellenico in Syros; these include a circular well 9-m deep with a stone lining and a stone-layered, mostly covered corridor with regular stone steps descending to the well from the north. The well and corridor walls converge upwards according to the characteristic ancient construction of underground works, thus providing greater strength against overlaid loads. This is a very strong indication that above the stone cover of the well and the corridor there was a backfilling of soil, as is roughly depicted in Eleftheriades’ drawing. The width of the well in the middle of its depth is approximately 1.17 m and at its upper end almost half of it; similarly, the corridor, with a maximum height of about 5 m, has at the bottom a width of about 80 cm, while at the top, it is much smaller, further reduced due to mechanical deformations.

At the lower end of the staircase, placed in the first step, a monolithic shield of 89 cm height protected the people using the well against falling into it and the well against pollution from the side of the corridor. The hole at the bottom of the shield indicates that the water level could exceed at least the 1ststep (as is the case now).

Two or more meters (2.05 m) above the level of the first step, there are two large square holes in the stone lining of the well, in diametrical positions, apparently for the attachment of a strong beam with a lifting pulley. Such beams, wooden or from stone, which usually seated on a pair of pillars above the well, are documented in ancient illustrations, while other ones, usually from marble in the form of Ionic columns, are preserved in a large number until today, revealing in detail the measurements of the pulley housings and the pulleys.

The holes in the well under study are almost 25 cm wide (measured perpendicular to their axis) and about 22 cm high. Therefore, the cross-section of the beam bearing the pulley could have been 24 cm wide and 21 cm high.

If this beam was from marble, detaching it from its place would only be possible by breaking. This process would, however, certainly leave enough marble pieces in the casing. The absence of such pieces leads to the conclusion that the beam was wooden.

All the original structural elements of the well (walls, steps and roof) are constructed with varying size pieces of good quality, almost white limestone rock, or rather marble ( “amarmaropetra” according to Eleftheriades) which is sufficiently cleavable to allow relatively easy cutting, without being weak and susceptible to damage. The stones, sometimes longer than one meter, are worked on their faces by needle in the perfected and, at the same time, efficient way of the ancients. The bearing surfaces, formed either by perfect slitting or by special carving, are so flat as to ensure optimal transfer of loads and very good appearance of horizontal joints. The ends of the blocks are also worked with the needle to form vertical or approximately vertical thrust joints, but not rarely they retain their natural form and the interspaces therebetween are filled with smaller suitably hewn stones or boulders.

A newer dry masonry, with projected stones at regular intervals to facilitate going down, blocks the aisle above the 6th step (countersupporting the deformed ancient walls). Two more steps, the last ones according to Eleftheriades’ drawing, are detected through the gaps of the dry-stone structure. However, it is not yet certain that there were not even higher ones. Confirmation for or against the existence of such additional steps is not possible without removing a substantial part of the backfill.

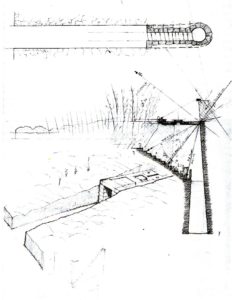

Further even north and closer to the surface, the corridor continues as a 2-meter wide road, and about 30 centimeters are carved in the rock. This road (BT), although covered by a thick aggradation, it is followed to almost twenty-seven meters to the north of the well but then blends with the surrounding corroded natural ground. Removing the aggradation from its northern end, where it should not exceed half a meter, will allow not only the measurement of length, level and possible tilt to the north (for natural runoff), but also to test the assumptions for the number of steps of the corridor.

At this point, a noteworthy feature of the well must be mentioned: based on the visible parts of the corridor and the rock-carved road, these two major elements are exactly aligned at the astronomical meridian of the place.

Another remarkable feature of the well is that it is in the middle of an area that has resulted from the excavation of the southward ascending rocky ground (25-27% slope).

The southern boundary of the excavation is about 20 m from the well, the west about 9 m. The eastern boundary may not be visible because of the backfill but is assumed to be symmetrical to the western one with respect to the well. The depth of excavation at the well is about three meters. Due to the new tiers of backfill to the south of the well, the original ground configuration within the excavation is not distinguishable: was it horizontal or staggered as the newer subsoil on it? While the few indications favor the second case, only the question of the level of the initial configuration immediately south of the well remains critical.

3. The covering of the corridor

Three of the cover plates continue to exist completely in their positions: K2, K3, K4, located at a uniform level. Between the K2 and K3 plates there is now an uncovered space of 53 cm, but this was initially covered with an overlying element (as indicated by a related treatment of the northern edge of K2). In Eleftheriades’ drawing (1875) this element, a stone plate, seems to be still in its place. To the north of K4, a dense reed clump excludes the presence of a subsequent plate in place, but it is not unlikely that related fragments that felt are now hidden buried in the later backfill of the corridor.

It is more likely, however, that the sought elements are identified with two plates fitted roughly on and adjacent to K4. One of them (K5) should have been originally immediately north of it. The other one (K6) is probably the one that used to overlap the gap between K2 and K3. This plate must have been removed from its position to allow the northern half of the corridor to be filled with the dry masonry already mentioned and to allow the remaining area to be accessible. After the completion of this work, the gap between K2 and K3 must have been covered again. Pollak says that when he visited the site, plates parallel to the well prevented the observation of the underground area and that he asked the owner to remove some; this was done. However, as K2, K3, K4 do not show any signs of previous movement, it is obvious that the farmer only removed the one overlapping the gap between K2 and K3. The removed plate should have been one that had replaced the original (K6), certainly a smaller one.

4. The covering of the well

The situation is different above the well itself, where today’s circular opening gives the impression of an almost normal but rebuilt form with irregular stones. However, a more careful examination of these stones reveals that they are not foreign elements, but merely the residuals of an authentic marble cover. Their present irregular form is the result of a destructive removal of its middle part to make the well accessible from the top above. At the time of writing the original report (Jan. 2005), the available observations left room for the representation of a two-stone cover (‘.. From the repetitive and exhaustive examination of the residues, but also of fragments that may still lay in the well or at some place of deposition of the products of a cleaning that happened around 1880, it might be possible to say definitively whether its ancient cover was a single stone or consisted of two stones. The latter possibility seems at present much more likely due to a considerable difference in thickness and length of the west and east parts of the cover: a longer one (90 cm) and somewhat thicker (around 20 cm) plate to the west of the well and one somewhat shorter (around 80 cm) and thinner to the east of … “). During the recent re-examination of the residues, the hidden limits of the well covering were searched for gaps in the newer wall built on the top of it. These limits were found at distances to the east and west of the shaft much smaller than those that one would expect for a two-stone covering which, thus, would be composed of two interposing plates. Undoubtedly, the remnants belong to a uniform triple plate cover, whose outline can be drawn with good approximation thanks to the hidden parts found in seven different positions. It is a quadrilateral of an average 103 cm in length and 94 cm in width at its west and 80 cm at its east sides. These two so unequal sides are similarly oblique, forming with the other two sides acute and obtuse angles, characteristic of the structure and layering of the rock of origin, which is common to most other well-observable pieces of the same work. The gradual and yet slight decrease of plate thickness to the east is irrelevant. In any case, the well was initially accessible only through the corridor and its present form with an orifice at the top is the result of a late reformation, which is even dated (1882) with an inscription engraved in the best part above the mouth. With the new findings, the old questions were resolved, but other questions were born connected with the reforming of the well (1882), because instead of removing the whole plate (which as we have just seen is not very big), they preferred to break it, getting into much more trouble and harming to some extent the good appearance of the well. The only logical answer would be that the newer wall, sitting on the perimeter, already existed with the backfill. But this explanation raises a new question: why there should be such a wall in the form of a well mouth, while the well was completely covered by the slab. One explanation is possible: the plate already had an older chiseled aperture enough for the passage of a vessel, and therefore the present opening is an all-around enlargement of that one. This explanation also illuminates the two-part construction of the newer wall across its height (see note 8). At this point a new question arises again: when was the hypothetical small hole possibly made? with the first recent reuse of the well (1875), or perhaps earlier? In this respect, it is worth mentioning the following: a) in the Eleftheriades’ drawing (1875), the hypothetical hole is not mentioned, but it does not even mention the plaque itself. The latter would require a complete revision of the foregoing conclusions, if it did not coincide with the fact that in the same drawing, cover plate K4 also appears to be missing; but this obviously remains in place without ever being removed (the certain inaccuracy of the old drawing may be attributed to the unfamiliarity and rather unfavorable circumstances in which Eleftheriades drew it up, or perhaps to some misunderstanding when it was copied on behalf of the German edition); b) the upper end of the well lays exactly above the beam that bears the pulley; and therefore it would not be possible for a small hole above the well to have existed since the first antiquity, but at most in a later period in which the original system of drafting water was no longer used.

5. Special features

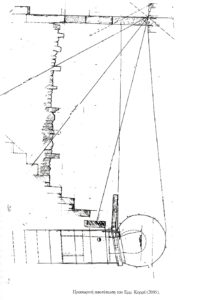

The careful observation of the monument reveals deliberate deviations from single axiality, verticality, etc., which are described below as special features. The center of the shaft is 15 cm to the left (east) of the corridor axis and as a result the section of the circular circumference of the well intersected by the corridor is an arc with a chord oblique to the east-west axis. This chord has defined the front of the 1st step, which is therefore also oblique. The obliquity of the first step resulting from the well eccentricity with respect to the corridor is not an isolated phenomenon but, progressively reduced, is repeated in the following steps, which are therefore trapezoidal, always wider at the western end and narrower at the eastern.

The first step with a left turn of 150 degrees has a width of 35-44 cm, the second with a left turn nearly 100 deg, has a width of 38-40 cm, the third with a left turn 80 deg, has a width of 37-40 cm, the fourth with a left turn 70 deg, has a width of 33-34 cm, the fifth with a left turn 60 deg, has a width of 28-33 cm, the sixth with left turn 30 deg has a width of 30-34 cm, while the seventh, the only non-turning step, is much wider (average width 56 cm) and may be considered as landing step. There is another step, the last one in the Eleftheriades’ drawing, which at present is not easy to measure precisely.

In Eleftheriades’ drawing, the 7th step exhibits a very remarkable carving at its top along the edge and has a small circular hole near its north-east corner (marked with the letter “Ξ” [“X”]). These data were confirmed in the recent survey, but it is not possible to observe and therefore to interpret the hole. Most likely, however, it was the socket of a door panel to secure the underground space of the well.

The obliquity of the steps, or in other words their left turns, does not seem to be merely a mechanical repetition of the obliquity of the lower end of the corridor. If the obliquity itself was not desirable, and the upright position of the steps with respect to the shaft was preferable, the builders would have done the second. In contrast, everything indicates that the left turns of the steps and the shifting of the shaft towards the left is an essential part of the design with pure ergonomic utility. People went down carrying an empty amphora, but it was more difficult on the way up for the additional reason that the amphora was full of water. With the amphora generally on the right side, the person stepped further to the left than the middle, that is, closer to the western wall of the corridor, while the amphora remained close to the eastern side, that is, on the imaginary line passing through the center of the well and at the same time from the point of sinking the amphora in the water. On the way up, the left turn of the steps reduced the risk that a longer amphora could hit one of them. The fact that the person climbing the steps carried the vessel on his or her right side is proven also by the existence of a circular carving for resting the amphora set up in the second step (“M” in the Eleftheriades’ drawing), whose center is 25 cm from the right side of the staircase. This carving will also concern us later for reasons unrelated to the use of the well for supplying water.

The person, while standing in the first step, used the pulley by pulling the rope from its right side down. At this point, it should be noted that in the truest testimony of the beam casings, the beams also had a skew in the transverse axis and even more pronounced than that of the first step. This brought the rising amphora even closer to the person, making it easier to pull the weight over the shield towards the staircase.

Because of the shield upon it, the 1st step has the minimum necessary surface. The person had to stand on it with the feet turned in a certain position, turning to the left, that is, ready to lift and bring the vessel towards him or her, turning immediately afterwards even further to the left to start climbing the way up. In this way, instead of a turn of the body at an angle of 180°, it performed successively many smaller turns up to 20° in the way down, another 20° at the stop near the pulley, another 60° during pulling the vessel above the parapet, another 60° for the start the climb. To complete the 180o, there was still a twisting of the body by 20o, but this could occur slowly through the climb so as to further reduce the risk of the vessel hitting one of the steps.

The reference to the special features of the design concludes with the observation that like the steps, the cover plates also exhibit obliquity albeit a constant one (about 7ο), because their sides are generally parallel. This obliquity is smaller than that of the first step and higher than that of the upper step.

As it is common in similar works, the side walls of the corridor are tilted, with the obvious purpose of making the construction of the roof with the cover plates easier and more robust. Due to deformations, the tilt angle is now completely changed. The issue of the original form is discussed below.

6. Mechanical deformations—approximation of original form

Because of pressure from the softer materials on the back, the walls are shifting with a strong bending towards the space of the corridor and therefore it is not possible to measure the basic dimensions or the inclination.

In the attempt to calculate the original dimensions, valuable clues are provided by the upper lining stones of the well, whose carved face was part of a conical surface. Two of them, due to the length and regularity of their curved part, were considered to be more useful in the calculations based on:

- the assumption that these stones had a common center of curvature;

- the determination of the radius and center of curvature of the face of each of them;

- the co-examination of theoretical rearrangements of the stones such that the curvature centers become coincident;

- the selection of that rearrangement which reconciles the two stones with a theoretical rearrangement of the walls of the corridor.

With reservations for possible corrections if additional indications become available, the upper diameter of the well is estimated to be about 73-74 cm and the upper wall distance is about 63 cm, while their bottom distance is about 81 cm. Therefore, the slope of the side walls was an average of 1:30, which based on the ancient measurement standard can be specified as 1 finger every two feet of height (ie 1:32). The slope of the walls is of particular interest because is greater on the south side, almost nullified to the north (i.e., towards the corridor), and at the corridor is affected by the height reduction of the walls to the north as a result of the staircase.

Based on the measurement system used in Cyclades, the width of the corridor is estimated to be equal to 2% feet (sic) and the height of the steps equal to 14 fingers (26 cm), while the height of the armor is exactly three feet. Similarly, the diameter of the well at the height of the first step seems to be equal to 4 feet.

One issue that cannot be considered at present is that of the form of the northern end of the corridor. Was it a simple opening or contained a door frame to better manage the use of the well? The circular hole on the 7th step is consistent with the second assumption.

7. Construction stages

The stages of construction of the ancient well can be represented as follows: a) hydrological investigation of a wider area, search for indications of the most likely location of underground water (ground water, geological layers, surface flora); b) technical study (calculations, etc); c) excavation of a horizontal corridor in the rock, over 27 meters in length, 2.3 m in width and maximum depth of six meters; d) excavation of a staircase and a shaft at the southern end of the corridor up to the point that it meets the aquifer; e) further, even deeper excavation of a well (another four meters) with simultaneous intensive pumping of the springing water; (g) stone-built lining of the walls up to the height of the staircase; (h) laying of stone steps and simultaneous construction of well and corridor walls, including the stone armor of the first step; i) placing of cover plates; (j) excavating and shaping the ground to the south up to 20 m from the well.

8. Age

The issue of the dating the well cannot be seriously considered unless properly dated fragments of contemporary vases are collected. For the time being, it can only be said that the technique of its masonry is that of the more common buildings of the 5th century BC.

The later history of the well is not apparent. A systematic investigation, however, based on broken vases mainly from its bottom could show the length of its use.

9. Discovery and reuse

The recent history of the well is better known, even though there are some inconsistencies.

According to Pollak: “… in 1870, architect, D. Eleftheriades, discovered and characterized as ancient the well that at that time was still buried with its upper stones to be the only visible part, while in 1875, he was sponsored by the then counselor of France, Challet, for removing the soil and cleaning the well. In October 1875, when he finished cleaning, Eleftheriades carried out an accurate documentation (including measurements and drawings) of this interesting building … ”

The related testimony of A. Fragkides reads as follows: “… at the time when counselor of France in Syros was ChaIIet, a farmer, picking up one of the reins that was caught on a stone while plowing the fields, observed a deep pit, after prompting from the counselor, he excavated the place and found the well … ”

Bypassing, at the moment, the disagreement between the two testimonies with reference to the identity of the person who discovered and cleaned the well, what followed immediately after 1875 is summarized below:

- Removal of plate Κ6

- Construction of the newer wall inside the corridor over the 5th step in order to countersupport the ancient parts of the wall that were bent; this resulted in the elimination of the ancient access way.

- A small hole carving on the plate above the well for its use from above (if this did not already exist from a more ancient conversion).

- Construction of a retaining wall one meter high around the perimeter of the plate east, south and west of the hole.

- The new well redevelopment and the surrounding area must be dated about 1880 or maybe later (see below).

- Increasing the height of the grooves of retaining walls and embankments around the well. The new wall rests slightly on that of 1875 and its southern part reaches a height of almost two meters above the ancient cover plate of the well.

- Construction of the two pillars for mounting the pulley, which stands at a height of more than three meters above the cover plate.

- Violently widening of aperture of the cover plate that existed till that day using a sledge or heavy hammer (known as a “heavy”); this because the rope wrapped around the pulley required space as it was shifting, thus exceeding the width of the hole.

The pillars are square with sides about 57 cm, height about 1.40 m and are almost one meter (97 cm) apart. The space between them is occupied by a straight horizontal marble plate whose top surface is almost two meters (1.97 m) above the ancient cover plate. At one of its edges, towards the mouth of the well, and about its middle, there are shallow markings like grooves; these bear witness of rope contact and therefore the drawing at times of water without the use of a mechanical means.

It should be noted here that these shallow grooves, mentioned above, do not overlay, as it should be, over the middle of the extended opening located two meters deeper but are projected so close to its perimeter to exclude the case of a safe retrieval of a vessel or container with a rope passing through one of the grooves, especially the eastern ones. So, the nice straight marble plate had been moved. However, as the pillars immobilize it, its previous position precedes the construction of the pillars. Probably it was part of the original wall, properly born over the original carved hole with its ends on the large elongated stones that crown the two legs, east and west, of that wall.

The middle of the flat surface of the marble is engraved with care with a calligraphic inscription: Hellenico – Ioannou M. Vakodiou – 19/3/1882. But it is not yet clear whether the marble was still in its original or current position when the inscription was made. This is one of the issues remaining to be clarified.

Works following the construction of pillars include:

- Construction of the small stone-built reservoir and the built-in trough, on the right (east) of the pulley, for every possible use of precious water.

- Construction of the small enclosure, which with its shaft in its south-west corner it also includes part of the long-buried ancient road and the ground leveling to its east, where still some low grape vines survive, also suitable for vegetable gardening requiring more watering.

- Landscaping of the rest of the area in the south with retaining walls and tiering suitable for vines and fruit trees.

10. Possible use of the heliotrope

Whereas according to the above, the form, the operation and the later stages of the well, at least for the time being, are sufficiently illuminated, there is still another issue not unrelated to the northern orientation of the corridor; it is that of the use of the well as a heliotrope which Mr. Louis Roussos is hypothesizing.

In regards to this question, let us note the following: the direction of the corridor to the north, justified probably by the fact alone that the ground of the region is tilted towards there, is suitable for, on the one hand, the definition of a line on the steps oriented towards the local meridian through the Polar Star, on the other hand, for the definition on it of the solstices through a beam of sunrays, for this purpose a additional small notch would be needed at the southern edge of the plate cover. The following evidence is still in favor to this:

- the staircase, with an average inclination of 38 degrees is approximately vertical at the plain of the ecliptic;

- the imaginary line passing through the circular socket of the second step and the southern boundary of the upper portion of the ancient wall of the well has an inclination of approximately 76 degrees, the same as the rays of the sun at this latitude in the summer solstice;

- the imaginary line passing through the edge of the 7th step and the southern boundary of the upper portion of the ancient wall of the well is inclined about 52½ degrees, the same as the sun rays at this latitude in the spring and autumn equinoxes;

- the imaginary line passing through the southern boundary of the excavation (20 meters south of the well) and the southern boundary of the upper portion of the ancient wall of the well has a slope of approximately 54%, sufficiently below the slope of the solar rays (~290=~56%) at this latitude during the winter solstice. If the upper part of the well was only half a meter deeper, or if the southern boundary of the excavation was not so far from the well, then in the winter solstice, the latter would remain in the shadow of the unexcavated opposite ground.

To the extent that the above would not be all incidental, the case of heliotrope operation seems sufficiently well founded. At present, however, a reservation is necessary because:

- referring to the aforementioned evidence 4, the altitudes of the ancient excavation immediately to the south of the well is not yet known; or stated in a different way, we cannot exclude (until the proof of the opposite) the presence there of a rock interrupting the sun rays to the well during the winter solstice;

- because the middle part of the cover plate in which a small slot for the passage of the solar rays is assumed is not preserved; and

- because the upward convergence of the walls is a strong indication of a backfill over the stone cover plates.

At this point, it is worth mentioning that long before the appearance of normal observatories, some rather unrelated buildings (eg large churches in Italy after the Renaissance) were used due to their size and rigidity as sites for the establishment of meridian lines and the definition of the meridian paths of the sun for different days of the year. The use of wells for a similar purpose by Eratosthenes falls within the same general category. It is of no wonder, therefore, that even other wells had, except from watering, also some astronomical, especially calendar use. The only necessary condition would be simply to have a descending staircase with sufficient northern orientation. Such use of the Hellenico in Syros is also very likely and deserves to be considered in the context of any purposeful archaeological study and its promotion as an extremely interesting monument of ancient technology.

11. Re-enforcement, restoration, showcasing

Today the surroundings of the ancient well encompass a dry ground expanse where only spines grow, and the aggradation of the ancient corridor hosts a dense windswept cluster of reeds. From the great, wide-shadowed fig tree that Pollak saw in 1895 in the southwest of the well, only corpses from its massive trunk remain fallen on the dried ground ever being fractured and disappearing, while the retaining walls are deformed and collapsing every so often. And yet this great place would still deserve to become a small oasis like it used to be, while much more should be done to restore and highlight the ancient monument.

Taking the above into account, a restoration and showcasing program could include the following:

- Surface archaeological survey of the wider region for relevant statistical conclusions (regarding the type and duration of use of space and the wider region);

- Cleaning the well and studying the findings from it. Search for fragments and attempt to repair the cover plates;

- Unburying and archaeological excavation of the lower aggradation of the stone-cut corridor and of the northern end of its stone-built part;

- Search for fragments of the cover plates;

- Metal countersupport of the stone-built walls in the place of the maximum deformation and then removal of the newer wall (end of the 19th century);

- Documentation with an accurate drawing on scale, accounting for deformations and accurate depiction of the restoration of the full original form;

- Seeking evidence of its usage as a heliotrope and a strict comparison of the original geometric features of the monument and of the solar passage corresponding to the precise latitude of the monument;

- In case of confirmation of the presumed astronomical use in antiquity, restoration of the initial level of the surrounding ground after demolition of the newer over structures; otherwise, restoration of the ancient monument, perhaps without the demolition of these structures, which it would be possible to preserve them as well.

- Production and distribution (in the archaeological museum of Ermoupolis) of a brochure, as well as a digital disc under the auspices of the Ministry of Culture.

The views of professors I. Stephanou and P. Touliatou

Based on what has been done so far, an effort has been made to gather all those elements which, although they cannot be considered yet unshakable proofs, are substantial and significant indications that this Well is not a simple well for pumping groundwater, nor a water collector to serve the day-to-day needs of the residents of the surrounding areas.

Its highly elaborate construction and its special Architectural, geometrical and technical details may not justify a simple use of an agricultural well. Besides, these same details in many cases lead more to the exclusion of such possibility. For these reasons and beyond the conclusions of Professor of History of Architecture, M. Korres, which are described in detail in his report, Prof. I. Stephanou and Prof. P. Touliatos, Professor of Structural Engineering and Ancient Technology, insisted on the following points:

- First concerning the location of Panaylias: whereas during the Chalandrian-Kastri period there appears to be some township or settlement, since at the back of the same hill and towards the sea (Agios Loukas area) there are so many tombs found of this time, there are no indications for even some residential concentration during the 6th, 5th or 4th century BC. Any finds of ceramics or other funerary offerings there belong to the prehistoric era. That is why, when discovered in 1870, the Well itself was considered as a prehistoric find.

- The orientation from South to North of the whole construction with such precision also shows that it was done with particular caution (the orientation was not verified only by the magnetic north, but with the help of a gnomon it was shown that the axis staircase-access corridor precisely targets the Polar Star). Even if the topography of the ground led in such a direction, the precision with which the axis was carved as to coincide with the astronomical North cannot be attributed to mere coincidence.

- Also noteworthy, both for the extra construction difficulty and for also any hypothesis about its operation, is the eccentrical design of the stairway and the whole access route in relation to the circle of the well. The fact that the axis passing through the center of the Well and the Polar Star separates the corridor and the staircase into two uneven sections 1/3 and 2/3 of its width, this eccentric carving requirement of the corridor justifies the hypothesis that, since the construction functioned as an astronomical and solar observatory, and since the sun’s rays at the noon of each day penetrated through a hole or slit in the well and, depending on the season, ended at some step on the staircase or some point on the corridor, an observer with just a few minutes to mark the ray ending point and hence (sic) he should have been able to stand on the side so as not to block the light path with his body.

- The elaborate workmanship, the carving of the internal surface of the stone blocks of the well, the prepared placement of the shield slab are additional elements that do not justify the construction by villagers—of a small insignificant village at that—of such a work for simple pumping of water. The same conclusion could also be reached from the unergonomic design of the well (here the two professors do not agree with the ergonomic interpretation of Professor Korres) since an elementary last landing was not constructed that would allow the standing and comfortable moves of the user when he or she drew up water. On the contrary, the lower step has a width of about 18 cm, that is, so small that it does not allow the positioning of one foot pointing straight towards the well but only turned laterally. However, with one foot laterally positioned at the lower step and the other at a higher one, the pumping of water becomes particularly difficult and painful; this is something which cannot be justified in such a carefully designed and well-constructed structure.

- Still another feature that opposes the correct operation of a drinking-water well is the hole in the middle at the bottom of the shield separating the last lower step from the main well. There is no justification for the existence of this hole as an outlet for the overflow of the well because the level of this step does not allow outward drainage. But even if it allowed it, the hole would have to be at least 15 centimeters higher than the last water level, so that the dirty water of the corridor and the stairs would not enter the well. The prehistoric spring of Chalandriani (spring Lygeros), which still serves the Lygeros village, gives a picture of this use. In contrast, in the immediately above step and at the middle of its width, there is a hole at the bottom in the ridge, which probably serves to drain a possible overflow. Of course, neither the level of this step seems to give such possibilities (an excavation could likely assert it). Nowadays, the two lower steps are often in some seasons found in the water of the elevated waterbed of the well, hence, at least the lower step would often be covered by the water in antiquity as well. The possible explanation of the existence of the hole in the shield is that it was used to throw the water of the staircase and the corridor into the collector shaft. But this does not go hand-in-hand with the use of the well for drinking water.

- An indisputable sign of the astronomical and not simple use as a well of this underground structure is the existence of the two cavities on the axis drawn from the center of the well circle towards the Polar Star at the level of the second below and the 7th step, which coincide with the sun ray incidence points, the first at noon of the summer solstice and the second at the two equinoxes.

- The covering of the well staircase roof and part of the access corridor creates a further difficulty with respect to the solution for directly pumping from the ground level by some mechanism (similarly to how this solution was chosen from the late 19th century when the well was discovered again). In addition, since the well would also operate as a collector, the space about seven meters up to the surface of the soil would represent a not at all small quantity of water for a place where the lack of water was always a major problem. Instead, the hypothesis of the astronomical use of the structure can justify the need for it to be roofed since it would leave a slit or hole at the highest and most southern point of the housing to allow sunlight to penetrate exactly at noon of each day.

- The width of the corridor and staircase in the base and roof is particularly narrow and unergonomic for the carrying of a water vessel from a person, moreso to the highest level of the steps. At this point, the carrying of a vessel to the shoulder, the practice of the women of Syros over the centuries, does not seem possible.

- The creation of a straight access road about 30 meters long and even carved in the hard rock cannot be justified at all for a farm well in which the villagers went to get water. Any path or the construction of some rough steps in the fields would ensure a user-friendly and shorter access as it was done after its discovery in 1870. The north-south axis for access to the well necessarily points to the ritual use of the monument. A fact that argues in favor of its astronomical function, where during the solstices or equinoxes it might have been the place of rituals of religious or initiatory nature.

- Finally, another element that supports the cause of the astronomical instrument is the whole southward configuration of the landscape, which has undergone significant interventions by digging the rocks and the earth that would create an obstacle to the passage of the sun rays, especially during the winter solstice where the height of the elliptical trajectory of the sun is quite low.

As pointed out, these ten points could not be considered by themselves as unshakable proofs from the expert archaeologists, but we must admit that, as they have been stated, they are much more than mere indications that the Well Hellenico is not a simple well.

Undoubtedly, now is the turn of the archaeological excavation, the findings of which will be able to document the role and the function of this monument that is of great importance to Syros. Removal of the reed clumps and revelation of the access corridor, opening the entrance and finding or not of other steps, the search for the third suspected cavity in the ground (the point of incidence of the solar ray during the winter solstice), the evacuation of the well, identifying the source of the water supply (the water vein), finding any debris from the damaged roof of the well, etc., will allow a more accurate assessment of all findings and a fuller interpretation of the monument.

Our study so far leads us to the conclusion that this well served for astronomical observations and measurements. The fact that Ferecydes is a known philosopher related to the famous heliotrope in Syros leads to the hypothesis that likely he himself used this well in the form we encounter it today or in an earlier one for his astronomical observations. Still it is likely that he designed the construction and built it himself or one of his later students or school followers. Here, the precise dating will help a lot in identifying the ancient users of the well.

Investigation of the course of the well through the years can lead to unexpected findings. If this well pre-existed in a more primitive form and served the same purposes, the Homeric « .. Νήσος τις Συρίη κικλήσκεται ει που ακούεις Ορτυγίης καθύπερθεν, όθι τροπαί ηελίοιο»…which the director of the Alexandrian Library and the most important analyst of his epics, Aristarchus of Samothrace, interprets as “… where there was a heliotrope in which the movements of the sun were recorded, to prove true and then a lot until now unshakable data about the course of astronomical sciences or their origin to change them … “.

The fact is that one hundred and forty-three years after the discovery of the monument, we are now obliged to proceed to the complete excavation and completion of its study. It seems to have so much to tell us that we will only gain from this study. After all, nowadays, with the advancement of the sciences that support archeology, such as the natural methods of determining the chemical composition and structure of archaeological elements, or Artifacts, optical emission spectroscopy, atomic absorption spectroscopy, X-ray fluorescence, neutron analysis, infrared spectroscopy etc or methods of age determination of archaeological finds such as stratigraphy, radioactivity, obsidian hydration, optical or thermal luminescence, dating of rock fragments, etc. can provide information of the origin, function, role and importance of this monument.

Translated by Constantine Hatziadoniu