I was born and raised in the big city. I had spent the greater part of my life leading an estranged, alienated, incoherent existence in various European cities. In the summer I would head south to the Aegean islands. My inmost longing was to live permanently on an island. To savour this unique experience of life on a stretch of land, borne by an incessant and furious northern wind over the abyss of the sea. It drove me almost insane with desire to think of the wintry uniqueness of an island cut off by the tempestuous sea. I chose the Landscape of Syros because I felt it was substantial, hard, almost ascetic and so I became an inhabitant of Syros. On the one hand, a lively small town with an ample community, on the other a natural reserve on the northern part of the island, a harmonious natural unity, a pristine society of flora. It is these isles that gave birth to the Aegean civilization, regarded by archaeologists as the dawn of European civilization. [Cycladic; Keros-Syros culture].

It took me over 3 years to hike over the entire island of Syros and to photograph all manner of carving by human hand on its slabs and rocks. I photographed and archived this ‘chronicle of inscriptions’ that is part of the history of an island of the Archipelagos and gave it book form. I would wander on the dry mountain slopes among the shrubs and the sparse trees. The hum of bees that follow the itineraries of nectar, the Cichoriumspinosum that shivers under the wind’s breath next to the sea, small springs with aquatic plants, steep and rocky coasts, limestone and volcanic geologic layers, cliffs, sea caves that are homes to seals and sea turtles, gravel slopes, small ravines, sand dunes. In the course of this ramble on ancient stones I discovered a multitude of prehistoric carvings, drawings that were a groping first form of writing, representing symbols such as stars, snails, rhombuses, but also human figures and some form of measurement system, as well as impressions of the sea vessels of that time. I stood in awe before this many thousand-year-old ‘testimony in stone’ laid out at my feet, narrating everyday stories of the island’s inhabitants and of travellers in transit.

Carved on the island’s rocks was the continuity of the Greek language. I walked on millennia-old messages and faded inscriptions. I stood on faint rock carvings of nebulous equivocation, in hypothetical courtyards of ancient temples and Byzantine churches. I suspected just a few traces, perhaps only the steps leading to the temple of Asclepios, the future site of the temple of Isis and of the twin temple of Serapis. These were the protector Gods of seafarers and saviours of seamen that were tossed by the waves in their walnut-shell vessels, rowing in the same spot for hours on end in their efforts to hang on to dear life. This is where seamen – pilgrims, travellers, merchants, pirates- found safe harbour for water or food, lay in wait or sought refuge from the northern gusts, terrified and weakened as they faced the fury of nature and the elements. During storms, and among thunderbolts that pierced the roiling surface of the sea, in the lightning and deafening thunder, in the fierce wind that howled like an enraged beast, under the icy hail, the torrential rain, the ferocious waves that engulfed the vessel, the furious sea and the air that gave birth to whirlwinds and whirlpools and sea monsters, in the deep and treacherous currents that dragged the ships off course, in straits that thrust them onto the rocks and underwater reefs that waited patiently for the mind to wander.

Those battered by the sea would head for the bay’s calm haven. They would be safe as soon as they negotiated the cape and entered calmer waters. And then the same people, who had been through thick and thin, would engrave on the rocks their thanks to the gods who steered them to safety. They had come so close to drowning, to death, but had come through alive. They had witnessed the sea’s wrath and ferment and were now celebrating the gift of transient existence. Within human consciousness, the terror of drowning awoke ancient legends. The story of the God who, in his wrath, decides to wipe out humanity by drowning the Earth in water has been known since the Gilgamesh saga, as Assyrian-Babylonian, from the Old Testament, as Judaic, from Pindar, as Greek, and is has spread throughout the rest of the world, among the peoples of India, Korea, Indonesia, Australia, and North American Indians. This is the primeval terror of the wrathful God that these passing sailors felt as they dropped anchor in the bay of Grammata (Letters), and by carving the name of their ship on the stone, would put her under the God’s protection. Clearly, the small bay of Grammata, on the north-western coast of Syros, owes its name to the hundreds of inscriptions on the rocks dating back to distant antiquity, Roman times and Byzantium. This bay never ceased to provide refuge from the fierce northern winds of the Aegean to weather-beaten seamen and travellers throughout the centuries.

Most of the carved inscriptions are wishes. They contain supplications to the Gods so that they may grant fair weather or thanks for rescuing them from the storms. To Helios, Asclepios, the Dioskouroi, a precursor in antiquity of St. Nicholas, Isis, who stretched out her dress like a sail and steered the ship to safety, to Serapis, a deity of Egyptian origin who in Hellenistic times succeeded the Greek deities. Serapis was worshipped up until the 4th century AD and there was probably a temple to him at Grammata.

At the time, the ships that crossed the Aegean came from the coast of Thrace, the Dardanelles, the Black Sea, the islands and the coast of Asia Minor and the entire Archipelagos. But there were also ships from Syria, Cilicia, Egypt and the rest of the known world, and each traveller would pray to his own god, asking him to calm the rage of the stormy seas and to guide them to their destination. The inscriptions bear witness to the dangers encountered by the travellers who sought refuge at the bay of Grammata, when the elements made the Aegean furious and snakes sprung out of cape Cavo Doro.

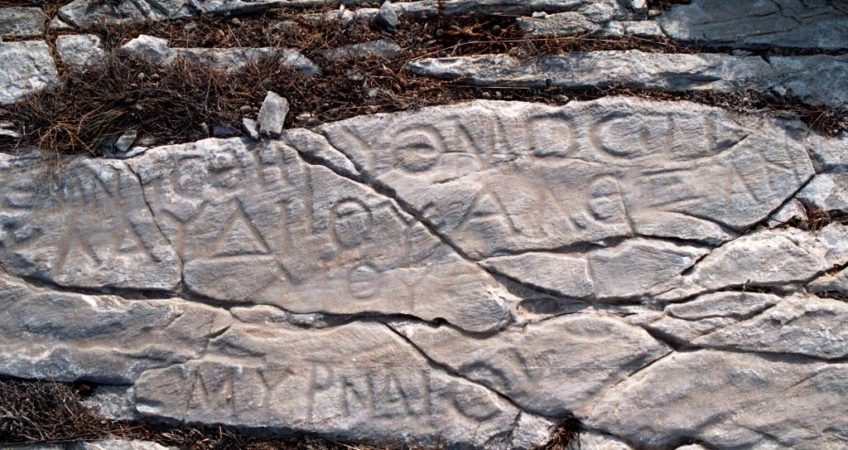

Today, there are about one hundred inscriptions preserved in the Grammata area. In the past there were more, but with time many have vanished –the writing faded as the rocks became weathered by wind and water. Some of the inscriptions are no longer legible. The archaeologist KlonStefanos was the first one to notice them. He camped out there in the mid-nineteenth century and proceeded to record and study them under adverse conditions. Stefanos claims that the inscriptions span an entire millennium,that is to say from the Hellenistic period to the beginning of the second millennium. On one of the inscriptions one reads the date (ς)φά, (993 B.C.), while on others there are indications of dates, though the absence of a uniform chronological system make them difficult to understand.

In the western part there is rocky promontory that looks out to the sea. It is precipitous and indicates that part of the island must have sunk during one of the cosmogonies of the past. The inhabitants of Syros call it ‘GriaPounta’ and on its tip there are Hellenistic and Roman inscriptions. At the foot of the slope that descends incrementally towards the head of the bay there was a quarry during ancient times. On the rocks nearest to the sea and on the surface of the stones rendered smooth by extraction there are Christian inscriptions, etched out in sophisticated calligraphy, from the time of the Byzantine empire.

1. Μιθρῆς Κολλυβᾶ

καὶ Ἑρ[μ]ογένης

[κ]αὶ Ἀρ[τ]εμίδ[ω]ρος.

2. σκοπὴ Χ— — —

[τῶ]ν πλε[υσ]άντων

[σὺ]ν — — — —

καὶ — — — —

5. [I]MPERPER….ELL…

Α]Ν[ΝΟ] ΕΞΗΣ

ΞΗ

6. ΜΙΘΡΗΣ

7. Ἀπολλώ[ν]ι[ος]

Ῥόδιος.

8. χαῖρε, Χλόη.

9. Ἀθηνοβίου

τοῦ ναυκλήρου.

10. εὔπλοια

τῷ φιλο-

σεράπι

τῷ(?) Ἰουλι-

ανῷ

Ἀρτεμισίου

Μειλησίω.

11. Phi[l]eros

—i[a]el.

13. [πα]ρ[ὰ] τῷθεῷ

ἐμνήσθη

[Α]ἴλ. Φλαβι[α]νὸς

πλ[έ]ωνἐντ[ῇ]

5

— — — — — — —

[κ]αὶ — — —

— — — — — — —

εὔπλοια.

14. ἐμνήσθηῬυθμὸςΤι.

Κλαυδίου [Ἀ]λεξάν-

[δ]ρου

[Ζ]μυρναίου.

15. L. Vettius Mella

L HII

16. <ἐ>μνήσθη [Ἀ]πολλῶς·

ἡμέθοδοςπαρὰτῷ

Σεράπικαὶτῇσκο-

πῇ.

17. Δ[ίω]ν(?) ἐμν[ή]σθη Ἀλεξανδ-

ρίδος.

18. Εὔπλαστος.

21. vita[lis

Διοτίμα

23. Σαρπηδὼν

Σαρπηδόνος

[ἐ]ποίει(?) μνισ[θεὶς(?)]

— — — — — — —

The top of the promontory on which the ancient inscriptions were carved may have been used as a ‘crow’s nest’ by anxious sailors eager to spot the onset of calm weather. The sea stretches out in all its breadth from this spot. It is also possible that this spot was used as a beacon, so as to make the bay visible during stormy nights. Or even as an observatory for pirates lying in wait in the bay, staking out unsuspecting ships.

Some of the inscriptions mention the names of men, captains, sailors or passengers forced by storms in the Gioura straits to seek refuge in Grammata bay and to await fair weather to continue their journey.

The majority of the inscriptions on the abandoned ancient quarry on the side of the promontory that looks onto the bay are Christian. They provide additional information on the people and the vessels that sought refuge there. After it became dominant, Christianity stamped out Asclepios, Serapis and all the other deities of antiquity, and their place was taken by Saint Fokas. Near the few remains of his church there are quite a few inscriptions with invocations for help. Most begin with “Lord, help us”, or with “Lord, save us”, and continue with supplications towards the Almighty to save the vessel and its passengers. A number of these include the name of the author, his father and his homeland, while in others one finds the name of the ship, its captain, as well as the month and year that the ship was forced to seek refuge in hospitable Grammata bay. Most of the inscriptions of that period are written in a corrupted Romanising alphabet riddled with erratic spelling that conveys a picture of public education in the Byzantine state. Also, the spelling errors in the inscriptions of the Hellenistic and Roman era can be explained by the loss of ancient prosody, that is to say the pronunciation of the ancient Greek language during Hellenistic times. Many of the inscriptions differ in their formal aspects: some invoke God, Saint Fokas, and the Aghioi Pantes(All Saints). Others express gratitude to God for having saved those at sea. In yet others there are wishes for fair winds and following seas, while another refers the inauguration of a small temple in the area, now lost.

Many of the Christian inscriptions are set within square frames imitating tablets with handles (tabula ansata). Some have a cross at the beginning, while one is decorated with a menorah, indicating that it was carved by a Jewish traveller. There are carved symbols near these inscriptions: pentagrams, pomegranates, or a capital letter Φ. Also a plumed helmet, a cross within a circle, an A and an Ω.

The inscribed names are mostly ancient Greek, such as Eulimenios, Leontios, Diotima, Eunomios, Aster, Makrobios, Synetos, Chloe, Megalonemon, Metrodoros, Sophronios, Isidoros, Philaletheios, Euplastos, Herakles, Apollonios, Oinoe. Philalethios appears as the owner of a vessel that dropped anchor in the bay and was from the island of Andros. The homelands recorded for those who carved the inscriptions are Andros, Paros, Ephessos, Melos, Pinara, Pelousio and Miletos, while their professions or offices are indicated as sailors, quartermasters, soldiers, monks, a kentarchos (centurion) named Dometios, a chiliarch (commander of a thousand) from Ephesus named Eulimenios, a hypatos (consul) named Stephanos. It is nevertheless unclear if this is the same person who is mentioned in a seal found in Calabria with the inscription “Κύριε, βοήθειτωσωδούλωΣτεφάνωυπάτωκαιβασιλικώσπαθαρίω” (Lord, help your servant Stephanos, hypatos and royal spatharios) or someone else, as Klon Stefanos observes.

Α Ω -Εγώ το άλφα και το ωμέγα, η αρχή και το τέλος.

1. Κ(ΥΡΙ)Ε ΒΟΘΗ ΤΟΥ ΔΟΥ

ΛΟΥ ΣΟΥ ΓΕΩΡΓΙ

ΚΕ ΤΗΣ ΜΗΤΡΗ ΑΥΤΟΥ

ΓΕΩΡΓΙΑ ΑΜΗΝ

2. [Κ(ύρι)ε βοήθει τοῦ] δού-

[λου σου] Δωμετήου

κεντάρχου

κ[αὶ συμπλοίας αὐτοῦ. ἀμήν].

3. σύ, Κ(ύρι)ε, βωήθι

το̑ οἴκῳ μου

κέ μοι το̑ γρά-

ψ[α]ντι. ἀμή[ν].

4. Κ(ΥΡΙ)Ε ΕΥΧΑΡΙ[ΣΤΟΥ

ΜΕΝ ΣΟΙ ΟΤ[Ι Ε

ΣΩΣ[ΕΣ Ι]ΜΑΣ

……ΚΟΣ ΜΙΛΙ

ΣίΩΣ

ΕΝΠΩΡίΟΥ υπ[π]ώνο[ς

5. ὁ χῶρος [τ]ῶν ἁγίων [πάντω]ν,

σῶσαι [τὸ] πλοῖ[ον Μ]αρί[α]ν μετ[ὰ] τ-

[— — — ἐ]στιν (καὶ) Ἰω[ά]ν[νου]

ν[α]υκλ[ή]ρου (καὶ) [τῶν] συνπλ[ε]όντω[ν]

[ἐν α]ὐτ[ῷ].

6. Κ(ύρι)ε σ[ῶσο]ν τὴν σύ[μ]-

[π]λοια Στεφ[ά]νο(υ)

(καὶ) Ὑπάτου. ἀμήν.

7. Κύ(ριε) σῶσων τὸ πλῖ[ον]

Γεωργίω{ν} [κὲ] Πέτρο να[υ]-

κλήρων με[τ]ὰ τ[ῖ]ς συ-

πλύ(ας) αὐτοῦ Μιλισίων

(καὶ) Πιλου[σ]ιανῶ(ν). ἀμήν.

8. Κ(ΥΡΙ)Ε ΣΟΣΟΝ ΤΗΝ ΣΥΜ

ΠΛΥΑΝ ΙΣΙΔΟΡΟΥ

ΑΠΙΚΡΑΝΤΙΟΥ ΓΥΑ

ΡΙΤΟΥ ΑΜΗΝ ΧΡΙΣΤΕ

9. Κύριε βο[ή]θει τῷ δούλῳ σου

Μακροβίῳ Μαβ[ρ]ι[κ]ιανῷ,

[καὶ —] συπλ[οί]ῳ. ἀμ[ήν].

— — — — — —ρίων

— — — καὶ — — —

[π]λ[οια]ν [τὴν ἐ]ν [τ]ῷ πλ[οίῳ]

κ[α]ὶ [τοὺς αὐτοῦ(?)] συνπλ[έοντας].

10. Χρ(ιστέ) βοήθει τῷ δούλῳ σου

Εὐλιμενίῳ

Ἐφεσίῳ χ(ιλιάρχῳ)(?) τῆς

[Ἀ]σίας καὶ τοῖς συν-

πολίτες τοῖς αὐραρίοις.

11. Κ(ύρι)[ε] σο̑σον τὼ

πλοῖον Μαρία

Ἰσδόρου Πι-

να[ρ]έως.

12. [Κ(ύρι)]ε σο̑σον πλῦον Σεργίου [ὀπτ]ήονος(?)

καὶ ἄρχοντος [․․․․․ μ]ετὰ

το̑ν πλεόντον ἐν αὐτο̑. ἀμίν.

․․ Γρ[η]γορίου <ὑ>πατικοῦ.

13. Κύριε βοήθι τῷ δού-

λῳ σου Γοργονίῳ

Παρίῳ

κὲ Ἰσ— —.

14. ΚΥΡΙΕ ΒΟΗΘΗΣΟ]Ν ΠΕΤΡΟΝ

……………………………ΣΩΣΟΝ

τὸ σκάφος Μαυριανοῦ ναυ(κλήρου)

καὶ Ἰω(άννου) ἀδελ[φ]οῦ Μ[αρ]οννιτ(ῶν)

(καὶ) το̑ν ἐν αὐτο̑ ναυτο̑[ν]

Κυρικίου (καὶ) Ι[ο]ύσ[τ]ου. ἀμίν.

15. Κ(ΥΡΙ)Ε ΒΟΗΘΙ ΤΟ ΔΟΥ

ΛΟ ΣΟΥ ΕΥΝΟΜΙΟ

ΚΕ ΠΑΣΗ ΤΗ ΣΥΝΠΛΟΙ

Α ΑΥΤΟΥ ΝΑΞΙΟΙΣ

16. σῶσω(ν) Κ(ύρι)ε πλύω Ἰωάννου

[(καὶ)] Μαρτυρίου Μηλ<ί>ων

μετὰ τῆς συνπλύας αὐτοῦ.

ἐκατεπορ<εύ>σαμεν μινὴ

Ἰαννουαρίο — —

17. ΧΡΙΣΤΕ ΒΟ(Η)ΘΗ ΤΩ

ΔΟΥΛ[Ω ΣΟΥ.………

………………… ΝΩ ΤΩ

…………………………

18. Κ(ύρι)ε κ[αὶ] [ἅ]γιε Φωκᾶ σο̑σο[ν]

τὸ [πλ]οῖον Μαρίαν καὶ το-

ὺς [π]λέοντας ἐν αὐτο̑

— — — πηδάλιο — —

— — — — — — — — — —

20. Κ(ύρι)ε σῶ(σο)ν τοὺς

δο(ύ)λους <σ>ου Θρε-

μίστα(?) [Ν]αξίους

καὶ πάντων σὺ[ν αὐτ]-

ῶ <(καὶ) Ε>ὐνωμί[ου τοῦ]

γ<ρ>άψα[ντος τὴν]

[ε]ὐχί[ν]. ἀμίν.

21. Κ(ύρι)ε σῶσω τὸν δ-

οῦλό σου Σύνετον

στρατιώτη μετὰ

το̑ν συπλεώντο[ν]

αὐτοῦ Νη[— —]-

κου. ἀμή[ν].

25. Χρ(ιστέ) σῶ[σ]ω[ν]

[— — ἀπὸ] τῶν

διοκόν-

των με κ[ακο]ύ[ρ]-

[γω]ν. θ[εὲ] σῶ(σο)ν.

27. ΧΡΕ ΒΟΗΘΗ ΤΟ

ΔΟΥΛ….

31. εὐχαριστοῦμέ σοι Κ(ύρι)ε ὥτι ἔσω-

σες τῷ δούλῳ σου Ἀστέρι Ναξίῳ

κὲ πάσ[ᾳ] τῇ σοιπλοίᾳ αὐτοῦ.

[ἀ]μήν.

Of all the ships that sought refuge in the bay, only the names of eight are mentioned. Oddly, four of these have the same name: Maria. In fact, through the centuries, vessels propelled by sail or oar carrying people from all parts of the Mediterranean world passed from this small and isolated bay in Syros. Sailors, merchants, travellers, pirates, people from the Cyclades, Asia Minor, the Black Sea, Syrians, Egyptians, Romans, Carthaginians and Byzantines moved passengers or merchandise from one Mediterranean port to another and left their inscriptions or signatures on the rocks of Grammata. Today, the inscriptions are entangled with the signatures and graffiti of tourists from Larissa, Brahami, New York, Denmark, Germany, and Japan.

Even today people continue to use penknives or spray-paint to engrave and to write, to paint and to imprint, out there in the street, moments from their lives or chronicle the innermost desires of their hearts. They are illustrated or merely in words. They are laid out in a variety of ways -profane, pretentious and unpretentious. They use stylized recipes, imitate other styles and/or copy others. Others, who are gifted, use their own personal forms of expression. Yet all are different manifestations of the same need, the need to express oneself and to communicate. Which is the main purpose of the inscriber-draughtsman-writer, who craves exposure and confirmation, who wants to stand out, to be noticed, to be accepted. This is what millions of people want when they make art – naive, folk art, primitive art, unprocessed art – or the ‘criminal art of wall vandals’, and the art of ecstasy. What springs forth are subconscious works and frenzied creativity that seek to trace the lost innocence of civilization and reverberate with the voices of the past.

Translated by: – / Edited by Rupert Smith.