Fauna

The fauna of Syros consists of a wide range of species from birds and reptiles to rich marine life. In this life we delve into the wildlife of Syros, focusing on the native and migratory species that inhabit the island and the waters that surround it.

The Mammals of Cyclades

3 August 2016

by Achilles Dimitropoulos

CONTINUING THE TRIBUTE to the fauna of the Cyclades, Syros Letters are now attempting to approach a less known and least studied group, the Mammals.

The first references to this issue were made by Tournefort (1717), Erhard (1858) and Heldreich (1878). To date, the related works are an exception in the international bibliography. The current data on land mammals and micro-mammals are due to Yannis Ioannidis, and for the species Dryomys nitedula, are due to B. Chondropoulos. Today’s tribute responds to the need for the people of Cyclades to know the Mammals of their area, a need that becomes obvious when we find that many people are unaware of, for example, the fact that in our islands there are animals like Asbos (skank) or that they think of whales as rare visitors; even a few years ago, the presence of the Monk Seal in the Aegean Sea was known almost exclusively to the fishermen; most of the islanders, but also in school textbooks, insisted that seals only exist in the northern seas!

On the contrary, occasional references have been made to species whose existence in the Cyclades has not been proven, such as the Mustelanivalis (Nyfitsa), in species whose recording is due to erroneous recognitions, such as Tsakali (coyote) of Tinos, which is none other than Asbos, and to species that, if any, seem to have disappeared, such as the Hare or Wild Hare in Syros. Besides, it is to be expected that future investigations will add other kinds to the list of species, especially bats, for which there is a lack of modern data from the Cyclades, with the exception of two very widespread species.

The relative rarity of publications for mammals in the Cyclades is probably due to the fact that their number is small. Species that are more common or more observable, such as the Hedgehog, catch the attention of the inhabitants and are more familiar, while others, more shy or hiding, like Asbos, go unnoticed. It is, of course, known that Mammals, in general, are particularly difficult to observe, usually more so than birds and reptiles. Most of them are nocturnal and hiding creatures, who systematically avoid man, and their main means of defense is their acute senses. So even the locals, in places where some species are found, rarely see them.

Researchers, in their effort to identify the presence of certain mammals, rely mainly on methods of indirect monitoring or recording, and rarely in direct observation. By using and evaluating the so-called bio-flagging traces (feces, tracks, food remains, nests, etc.) that betray the existence of certain species, scientists identify the presence and activities of mammals in an area—it is on such traces that some testimonies of species in Cyclades are based. Especially marine Mammals, which only by chance can one can meet them.

In Cyclades there are some mammals that are carnivores, such as cats (Wild Cats of Syros) or have a significant impact in “forming” the natural environment of the islands where they live, like the rabbit but also—of course!—the goat or pig in many cases. There are also the foreign, imported species, such as the South American llamas, which were left free on Gyaros in the 1980s. Many species of mammals have a “bad name” in the Cyclades, either for rumored damage (Atsida, mice, Araskos) or superstitions (bats). The mammals, like all the other identity elements of the island natural environment, must be protected in any way.

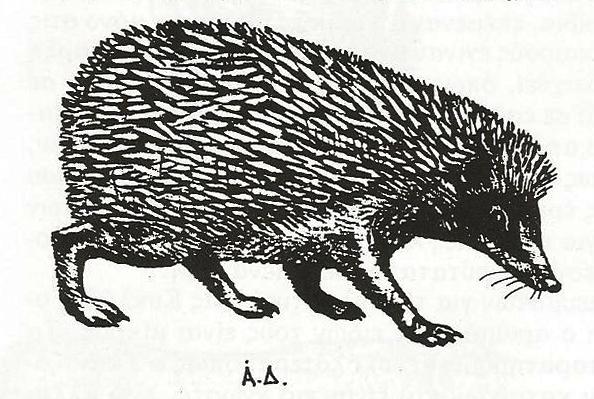

Insectivores (Insect Eaters)

This class, among the most primitive of mammals, includes about 370 species, belonging to 3 families: Erinaceidae-Hedgehogs, Talpidae-Moles and Soricidae. All insectivore animals have comparatively small, less developed brain and more developed chemosensory organs, while their pointed teeth testify that they feed on insects. In the Cyclades, from the representatives of this class only the Hedgehog has been recorded.

Hedgehog (Erinaceusconcolor). No relationship to hogs! One of the most common mammals in the Cyclades, the Hedgehog is seen often by men. Together with mice, rabbits and rats, it is one of the most popular and widespread animals on the islands. Its thorns (about 6,000) are nothing more than specially formed hair, which of course provide effective protection against the animal’s natural enemies, but not from the car wheels: hedgehog kills on rural roads represent a major threat to the species—it is a very common, macabre sight on the rural roads.

Hedgehog is active and moves usually during the night when looking for food. It is then observed relatively easily (by means of a flash light, for example). Although it belongs to the insectivorous class, it feeds on a wide variety of invertebrates (not only insects, but also snails or worms), sometimes vertebrates (lizards, snakes, corpses) and plants. When it eats, it makes noise: it smacks its lips when it chews snails or worms, and it makes characteristic sounds when it cracks beetles with its teeth. Hedgehogs mate in the spring, almost immediately after coming out from their winter hibernation. After a 5-6-week pregnancy, females give birth to 2-10 (usually 4-5) blind young ones, which, however, have few, short and smooth, whitish thorns. They abandon the nest when they are 3 weeks old and follow their mother.

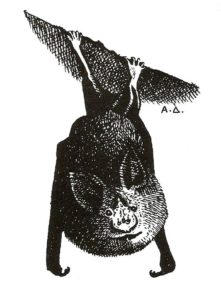

Winged Mammals

This class includes the bats, the only mammals that are capable of a real flight. Their “wings” consist of a thin, flyingmembrane that joins, in most species, the front and back legs, and in some species also the tail.

Bats are typically nocturnal animals, which are rarely observed in daylight. They feed on insects that they grab in the air, usually with their mouths, but sometimes with the help of their flying membrane. Bats eat their prey either while on flight or hooked on some surface. To orientate, they use sounds that they produce, ranging from 10 to more than 100,000 cycles, frequencies that the human ear cannot hear. The animals are oriented with the help of reflected sounds. We also know that some bats use specific cries to communicate with each other. The mouths and nostrils from where the sounds come, as well as the ears of the bats, have been shaped in different ways, characteristic for each species, and so they can be an important element for identifying the species of a bat, if we can see these animals closely. For example, many species of bats have an outgrowth in the inner part of the ear, which is distinguished as a fold or sharp formation, called a [tragos] and is seen in a variety of forms. The cries of bats can be studied with the help of special instruments that convert sounds into frequencies that can be heard by the human ear.

Our knowledge of the presence of bats in the Aegean islands is extremely incomplete, even though these animals are among the most prevalent mammals in the islands. The difficulty of a quick identification does not usually allow, except only to the experts, the accurate recording of existing species. Of the 23 varieties, which have been recorded in Greece, according to Corbet and Ovenden, very few have been observed today in the Cyclades. The islanders call all of them nychterides (bats), from the ancient name nychteris [night creature] (Nychterida in Syros, Nychteria in Kalymnos, Lychterida in Ikaria, Lycharida at Olympus of Karpathos, Tagarida and Tandarida in Leros). Erhard, in his work Faunader Cykladen (p.5), mentions a “new” kind of bat from Syros and he calls it Vesperertiliosoricinus.

The bats in the Aegean islands are mainly found in areas around humid caves and abandoned buildings, cottages and districts with old residences. Because they do not maintain their body temperature constant (normally around 35°–40° C) but adapt to the ambient temperature, the bats are completely dependent on maintaining their shelters, whether caves or ruins or abandoned homes. It is known that these animals fall into a mild, daily lethargy, from which they recover with difficulty, when they wake up are extremely vulnerable, as when they are disturbed during hibernation; then they quickly exhaust their energy reserves. For all the above reasons the protection of the bats in the Cyclades (and the Aegean islands in general) becomes imperative due to the constant decrease of their population, the destruction of the shelters (demolition of buildings, “exploitation” of caves), the inconsiderate use of pesticides, but also of the overall degradation of the natural environment.

Rhinolophus ferrumequinum. Quite large bats: Wingspan 0.33–39 m, body length 00.56–68 m. When hung with closed “wings”, it has a size of a human fist. Her flight is distinctive and reminiscent of a butterfly flight, with “tremulous” movements of the “wings”, alternating by gliding in the air. Noisy, especially near the colonies, makes sounds like shrieks and scratches. Every bat is in constant communication with others around it, crying. When it chases its prey, it often touches or even sits for a moment on the ground, grabbing walking insects. It falls into hibernation in caves, where it goes far enough inside and forms colonies, small or large groups. In the summer moves a lot. In Europe, it has been observed that it can cover up to 40 kilometers each day, looking for food. It has been repeatedly seen in Syros.

Pipistrellussavii. Small bats, body length 00.43–48 m, with distinctive color contrast between the color of the back, the white chin and chest and the black “face”; the hair on the back are dark with much lighter ends. It is often found in villages and towns, and forms colonies of 10 or more bats. This is one of the most common species of bats in the Aegean islands, with a distribution which in the Mediterranean countries includes North Africa and the Canary Islands, while in the east, it spreads through Asia to the Pacific coast. It has been observed in Syros.

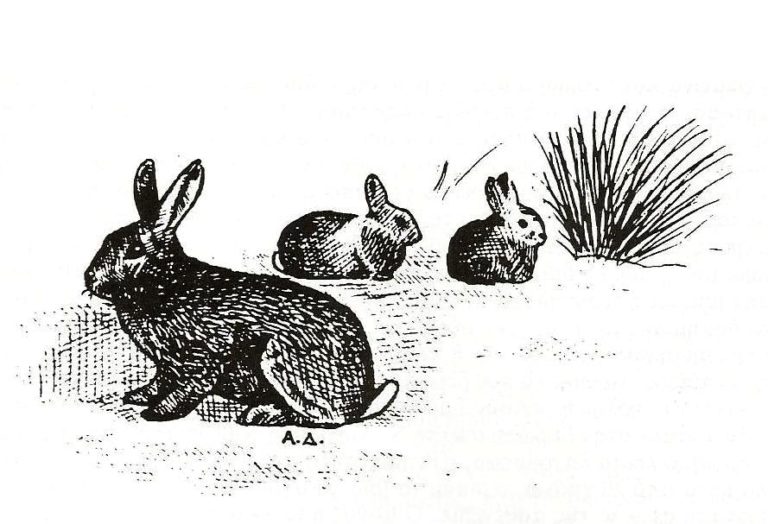

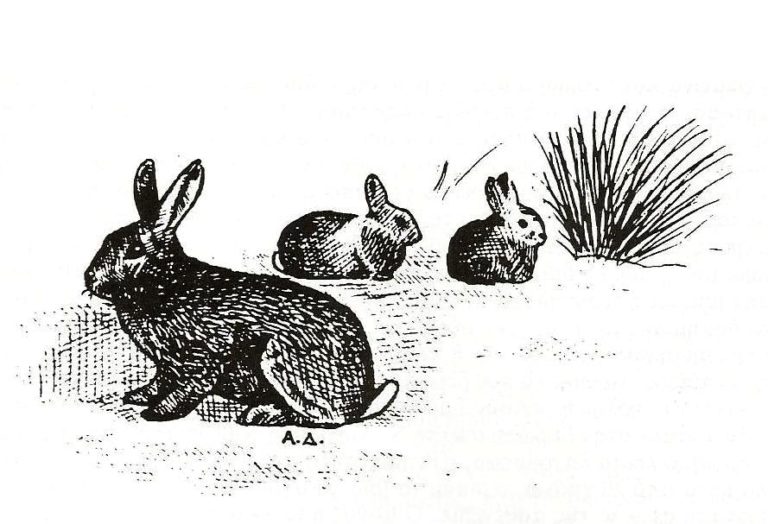

Lagomorph (Hare-Like) Mammals

Despite some morphological similarities with rodents, members of this class have nothing to do with mice and rats. In rodents there is always only one pair of incisors in the upper jaw, while in all the hares there is a second pair of incisors, behind the first. In fact, there is a parallel evolution of hares and rodents, to which any similarities are attributable, especially those observed in the skull, a result of functional adaptation. In addition to the well-known “representatives” with the big ears and strong, big hind legs, hares include the pika, a group with short ears and legs, nowadays seen only in Asia and America.

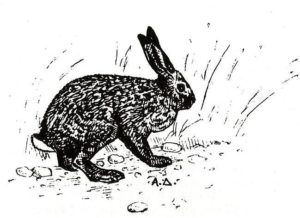

Rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus). The Wild Rabbit is a characteristic animal on the Iberian Peninsula, where it originates, but it has spread with the help of man across Europe, including our country, as well as in Australia, New Zealand, South America and hundreds of islands all over the world. The process for its domestication began in Roman times. All domesticated kinds come from the Wild Rabbit and have absolutely no relation to the hare. However, in many of the islands of the Cyclades, the inhabitants confuse the two animals and make no distinction between them: thus, both mainly the pet and the semi-wild rabbit are known in Syros with the name Lagos, the latter living freed from man in the wild (in Ano Meria, in Azolimnos, in Apyamata, in Gaidouronisi and in Stroggylo), even though it is almost certain that there is no (or has never existed?) a hare on this island, despite the fact that Erhard includes Syros on the islands of the Cyclades, where there are hares and not wild rabbits. Perhaps the rarely used name Agriolagos [wild hare] today in Syros is a verbal differentiation of the hares from the wild rabbits, which in any case also means a rabbit nowadays. It is very likely that the Hare disappeared from Syros, as it is certain that releasing rabbits in the wild, taking place now and in the past, is in order for food to be available to any shipwreck survivors. Nowadays, wild rabbits live in the following islands of the Aegean: Mykonos, Syros, Strongylo, Gaidouronisi, Delos, Thira (Platy), Ios, Leros, Kalymnos, Prasouda, Lemnos and Kos. The picture may not be very different from that given by Erhard around the middle of the last century [1800’s], when he mentioned that wild rabbits are found on the islands of Kythnos, Gyaros, Serifos, Kimolos, Delos, Mykonos and Folegandros.

Active, particularly at dusk as well as during the night, the Wild Rabbit does not hide so much on the islands, where it is not hunted, and it can sometimes be seen during the day. It is, however, one of the Mammals that are easier to observe. It digs labyrinthine tunnels into the ground where it hides and bears its young. It delineates its area with feces, which have a characteristic smell, secreted on the feces by special glands; the feces are laid in prominent places, within its “territorial” boundaries. The period of breeding in the Mediterranean countries begins during the winter and ends late in the spring, ie coincides with the period when herbaceous vegetation develops. After a pregnancy of 28-30 days, each female gives birth to an average of 4-6 young, who mature quickly and can mate when they reach 3-4 months. Each reproductive period a female can give birth to up to 30 young, whose mortality can reach at 80%. When there are no major predators, as in some barren islands, wild rabbit populations become so large that they directly affect the natural environment and destroy vegetation. In the case of dense populations, colonies of wild rabbits are structured in hierarchical order, where a strong male usually dominates on some females. If the population density reaches at extremely high levels, females in the lower ranks of the hierarchy do not give birth or give birth only to 1 young. When, in the mid-1950s, the terrible myxomatosis disease that infected the lagomorphs came to Europe from South America, the mortality rate of wild rabbits reached 99%, but after about 20 years, the wild rabbit developed genetic resistance to the virus. The only effective control of this animal’s populations can be done by its natural predators, given the difficulties and limited effectiveness of human hunting, especially in Australia’s typical example, where imported wild rabbits have multiplied to nightmarish levels and are still a problem in many regions of this continent.

Hare, Wild Hare (Ιepus europaeus). In the Cyclades, the Hare is rather a rare, unusual animal, with small, local populations, which are usually limited to specific places. Among the islands of the Aegean, these animals are generally more populated in Samos, Chios, Lesbos, Rhodes, Skyros, Naxos, Kos, where they coexist with the Wild Rabbit, as in the case of Lemnos (Kastro) and Andros, while smaller, geographically limited populations exist in Kythnos, Milos, Serifos, Sifnos, Amorgos, Tinos, Astypalea, Karpathos, Kasos, Kea, Kimolos and Paros. These figures do not differ greatly from those by Erhard, in the middle of the 19th century, when he reported that hares exist in Kea, Syros, Tinos, Milos, Paros, Naxos and Andros. It seems that there are no hares in Syros and Lipsi, while in the smaller islands of the Aegean it is possible that the presence of the Hare excludes the presence of the Rabbit.

Although there is certainly some morphological similarity to the Wild Rabbit, the Hare is a very different animal: its size is generally much larger than the Wild Rabbit and its ears are one-and-half times longer, with black tips. While the length of the Hare ranges from 0.48 to 0.67 m and its weight from 2.5 to 6.5 kilograms, the Wild Rabbit does not exceed 0.34-45 m and 1.3-2, 2 kilograms, respectively. Still the two animals have a completely different way of life: the Hare does not usually dig underground tunnels, but a shallow hall in the ground, it rests and gives birth hidden in dense vegetation, it is not as social as the Wild Rabbit; instead, it is a lonely animal coming out for grazing in the evening. For its defense, it relies both on camouflage, laying still on the ground, as well as on flight, since it can develop great speeds, constantly changing direction—at an angle of 80°, it can continuously monitor its predator. When it is frightened, it makes a distinctive cry. Hares are usually mating in early spring, in March and April. Each female bears to up to 5 young (usually 2), 2 or 3 times a year. In addition to its natural predators, from which it can more easily escape than the Wild Rabbit, the Hare faces hazards and additional pressures from anthropogenic causes, both directly (hunting) and indirectly (destruction and degradation of habitats, expansion of intensified crops, destruction of its shelters), as well as from a number of diseases, such as coccidiosis, which usually strikes populations of hares towards the end of the summer. Although some animals develop immunity, they do not cease to be carriers of the disease affecting the next generations.

Rodents

The largest in number class of Mammals, with the main feature being the presence of 2 incisors in the upper and 2 in the lower jaw, followed by a gap in the position of the canine teeth. The incisors grow continuously while the animal is alive as they wear out by the use. Although most rodents, with the exception of Spalax, which should not be confused with insectivorous moles, see very well and listen even better; they have highly developed chemosensory organs, and we would not exaggerate if we say that they live in “a world of odors.” Representatives of this class meet in all the climatic zones of the earth; the smallest of them is a relative of the house mouse, the African Musminutoides (0.5 m, 5–6 g), and the largest the South American capybara (1.2 m., over 45 kg).

Mus musculus domesticus or Mus domesticus. The most well-known and probably the most common mammal in the Cyclades, where it appears to exist in all the islands (including all the barren islands) and is transported with the help of man. It migrated from Pakistan, in the beginning on its own and then with the help of man, and its distribution spreads to the largest part of the world. Already during the 11th millennium BC, it had reached Israel, by the 7th millennium BC, in Asia Minor and by the second millennium BC, in Egypt and in Western Europe. It is an extremely diverse animal, which can have all the shades of gray and brown in color. The way of life and its habits vary likewise, depending on the area and conditions that prevail and certainly depending on the human presence (one of the proposed names is domesticus). At least 7 different kinds have been described by scientists, based on samples from Europe, and 5 of them have been considered to be quite different so as to be separate species. Mice living close to humans are omnivorous and reproduce throughout the year, while those living in nature (on cultivated land, Mediterranean shrub vegetation, or sparse forests) feed mainly on plant seeds, cultivated or not and on insects, and they mate from March to October. At each birth, after a 20-day pregnancy, it is possible to get 4–8 young mice, who become adult after 35–40 days.

Rat (Rattus rattus). The Rat like the Mouse is the most common mammal in the Cyclades, where it has been transported by humans (abounding in the hull of ships!) even to many barren islands and rocks, and it seems that, like the Mouse, it migrates, colonizing more and more areas within cities or even in the outdoors. As with the Mouse, coloration varies greatly, and there are individuals in all shades of brown, gray and black. Although it originates from India, the Rat has extended its distribution through the classical commercial routes of man, and already it was widespread in the prehistoric period. Today it is populous in the Mediterranean countries, but as we move towards Northern Europe, it becomes rarer.

The Rat living close to humans is an omnivorous animal, but in general this species shows a strong tendency to feed on plant food, mainly fruit, especially when living in the countryside, in cultivated areas (often away from residential areas). Some populations living in the countryside, in the Cyclades, feed on fruit (often carobs) and live on trees. Some scientists classify these populations in a separate species, Rattusfrugivorus.

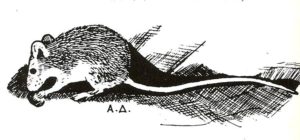

Armylagus (Dryomysnitedula). A small tree dweller, Armylagus is not easily observed and is one of the lesser known Mammals in the Cyclades. It seems that it exists only in Andros. Its body does not exceed 0,8–13 m in length and its tail is 0,8–9 m. The black mask around the eyes is its most prominent feature and is clearly distinguished as the only spot on the monochrome body that can vary in hue from light gray to brownish red. Its tail is covered entirely by dense hair. It is found in deciduous forests and shrubs from Poland and the Alps to India and China. It makes a tightly woven nest of branches, on the tops of the trees, but also among the foliage of dense bushes. It eats plant food as a very large percentage of its diet. In many areas of its wider distribution, it falls into winter hibernation; but this behavior has not been ascertained for the populations of Andros.

Araskos (Glisglis) [Dormouse]. Araskos is a widespread, tree-dwelling species, which it is difficult to observe (usually, it is seen accidentally), as it is active at night. It looks much like the previous species, but it is noticeably larger, and its black mask is limited to a ring around the eyes. Its color, uniform gray on top and pure white underneath, rarely varies, including brown-yellow tones, or in some samples a darker rib across the back. Its body is 0.13–0,19 m long and the tail is 0.11–0,15 m. It weighs 70–200 g. and, before falling into hibernation, it reaches 300 grams. In the Cyclades, Araskos has been observed only in Andros, where its name came from an ancient Greek origin (Araskos = Orescoos = mountainous, wild). It is also found in most of mainland Greece and in Crete, most of Central, Eastern and Southern Europe, absent from the Iberian Peninsula (except its northernmost extremity). It is imported to a limited extent northwest of London. Outside the borders of Europe, it meets in Russia, Asia Minor, as well as in the Middle East. Exclusively nocturnal, it prefers deciduous forests, shrubs and gardens; it is rarely found in coniferous forests. Noisy, it screams in several tones, especially when it is scared. It is often prey of various kinds of owl. Its winter nest, where it is withdrawn and falls into hibernation, is relatively low on trees or between shrubs, slits of bark or even on the ground, while, on the contrary, it builds its summer nest high up among the foliage of trees, in branch forks and holes. It falls into hibernation from October to April. It mainly eats vegetal food: fruits, seeds, walnuts, hazelnuts, tree bark (it is also considered to cause damage to walnuts and almonds, although responsible here is often the Rat). Depending on the area and season, it feeds on small animals at varying percentages: in some places, it is almost exclusively a herbivore and in other places chases chicks, small birds and insects. It grows fat for the winter, and in the autumn, before falling into hibernation, it gives the impression that it is more bulky than usual. At the beginning of August, the females give birth to 4–5 hairless and blind young ones, who open their eyes after 21 days, but continue breastfeeding for one more week. The pregnancy lasts about 4½ weeks. Araskos lives 6–7 years. The ancient Romans considered this animal a sought-after and expensive delicacy. They raised many of Araskos in large cages to later move them into smaller cages (gliraria, from the Latin name of the animal Glis) and there to fatten them regularly with acorns or chestnuts. When they reached the desired weight, they killed and ate them, as one would eat the most sought-after delicacy that a gourmet table might have. Even today it is known in England as Fat or Edible Dormouse.

Carnivores

Acharacteristic of all animals belonging to this class is the existence of developed canine teeth, suitable for holding on to the prey and to tear the flesh. Carnivores are divided into two major categories: those with fins (like seals, sea lions and sea elephants) and those with toes on their limbs (all known terrestrial carnivores, from wolf and dog to bears).

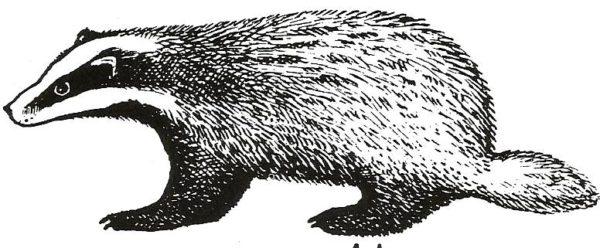

Asbos [Badger] (Melesmeles). Other names: Esvos, Arkalon, Jackal (Tinos), Azos (whence Azidi, Azida, Atsida). While, widespread in mainland Greece, Asbos has a very limited distribution in the Cyclades. It definitely exists in Tinos; we also have reports from Andros and Sifnos. It is easily recognizable, although it is difficult to meet the animal itself. Much larger than the Atsida, which does not exist in Tinos, but it is abundant in most of the other islands, it stands out from the light top of the body, which contrasts with the dark, almost black underside. The striped black and white head is characteristic. Overall length 0.65–90 m. Weight 6–17 kg.

It moves and searches for food during the night, leaving characteristic traces (turning somewhat inward, at least equal in width and length, and 5 fingers clearly visible). It is from these traces, but also from hair, e.g. left on barbed wire in the fields, that its presence in a certain area is established. One rarely meets it during the day, but rather more often at dusk. Equally characteristic as the appearance and the traces is its nest, a large, simple or complex tunnel, which can be very old and can have several exits (diameter 0.20-50 m); another characteristic is also the “outdoor toilets” near the nest: small holes in the soil, where feces are deposited. There is typically a large amount of soil under the nest’s exits. Asbos, being an omnivore, eats almost everything it finds at his nightly excursions, like the Hedgehog: herbs (fruits, nuts, seeds) and various animals (from insects and snails to rabbits, chicks and carcasses) are included in its diet . Quite a social animal, Asbos restricts its activities in the winter but does not fall into a real hibernation. 1–4 youngsters are born towards the end of the winter, after a prolonged pregnancy (there are intervals that the embryos do not develop). The new born stay close to their mothers up to one year after their birth.

Atsida [Ferret] (Martesfoina). Other names: Atsidi (Syros, Naxos), Azidas (Chios), Aitoulas, Aitoulakas (Andros), Zouridas, Zouria (Karpathos), Nyfitsa, Nyfitza, Marturion (It. martoro), Zerdabas (Turk.), Kolosyntecnaria (Crete), Mouse-Ferret (Samos). Atsida, as the Ferret is called in the Cyclades, is found in most of the larger Aegean islands. It is particularly populous in Andros, but it is absent from Tinos where one finds Asbos.

Smaller than Asbos, but also the wild cats in the Cyclades, Atsida has a length of 0.42–48 m and a weight of 1–2 kilos. It stands out from the uniform, dark brown color, interrupted by a light or white spot of varying extent in the chest; this spot may be very limited or even completely absent (more often in some, not all, specimens from Crete). Many dead specimens soon whiten from the sunlight in the upper part of the body.

Atsida is usually active during the night. The more it is pursued in an area, the more nocturnal habits it acquires. During the night, one can hear its characteristic, strong cry. It feeds on any small creature that it can kill, but a large percentage of its diet is made up of mice, while in the autumn it is more likely to eat plant food. It typically places its feces in visible spots, on stone walls or rocks.

It nests in cracks of rocks and openings of the ground or between stones, very often in villages and towns (mainly but not necessarily in abandoned buildings), like Chora of Andros or Ermoupolis of Syros (Haravgi). Since it moves around at night, its presence usually goes unnoticed, although in the Cyclades (Andros, Syros, Serifos, Kythnos, Naxos, Thira) it often grows into large populations and seems to thrive in residential areas and around human activities. Apart from the Cyclades, it has a wide distribution throughout Greece. Although it moves mainly on the ground, it climbs very skillfully and chases the same effectively on the roofs or trees. It mates late in the summer, but it gives birth in the next spring. The little ones stay near their mother for 4–7 months.

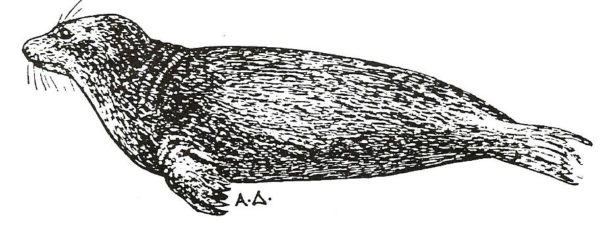

Mediterranean Monk Seal (Monachus monachus). The Mediterranean Monk seal is one of the rarest and most endangered species of Mammals all over the world. At the time that this article is written (April 1994), the latest calculations (Cebrian 1994) bring the total population to an extremely low level: 385–505 individuals survive, while in the greater Greece-Turkey-Cyprus-Libya region there are 120–250 individuals. Under these circumstances, only coordinated and determined efforts could save the species from extinction. The appropriate actions to date are rather limited geographically (in the Ionian and Sporades, for example), moreover it is not easy to extend or apply the same protection strategy across the entire marine area, given the monitoring and surveillance problems.

In Greece, the Seal was once not rare. Until the middle of this century, there were significant seal populations in the Ionian Islands, the Corinthian Gulf, the coasts of the Peloponnese, of East Greece, in Crete, Evia, the Cyclades, the northern and the eastern Aegean. In the systematic recordings of Marchessaux and Duguy, 1974–1976, at least 15 individuals were observed only around Syros, when the total population of the Cyclades was estimated at 70–90. However, since the first recordings, many things have changed. It seems that Goedicke’s pessimistic calculations, which predicted an overall decline in the 1980s, with many extinctions of local populations in the 1990s, are not far from today’s reality. With this in mind, the Mediterranean Monk Seal is Europe’s most endangered mammal, likely to fall below survival limits in the first decade of the 21st century. The Mediterranean Monk Seal is a large animal that can reach 3.80 m in length, but usually ranges around 2.20 m and weighs up to 230 kilos. Newborns are about 1 m in length and weigh 10–20 kilos. Coloration varies considerably from individual to individual. Although there are no specific rules, males tend to be darker and females often have white or yellowish spots on the underside of the body. The basic coloration can be brown, black, silver or gray, with or without lighter spots on the underside of the body. However, both totally white and totally black individuals have been found.

The diet of the Mediterranean Monk Seal includes fish, octopuses and lobsters. As a result, the fishermen have always considered the seals to be their “competitor”, and the attitude they held towards them ranged from indifferent to hostile. At present, no protection program for this animal can exclude the participation of fishermen who are in direct contact with the populations and refuges of the Monk Seal. Pressure on the populations has undoubtedly increased and, especially in the Cyclades, seals are becoming increasingly rare. After 11 months of gestation, the female Mediterranean Monk Seal bears one child every 2 years, which it breastfeeds for 6 weeks. Most births occur in September or October. The life of the Monk Seal is estimated at 30–35 years.

Ruminants [Regurgitating Mammals]

These animals are herbivores with rumination as a common characteristic, from which they are named. This is an unusual way of digesting due to the peculiarity of their digestive system: the stomach consists of 4 chambers, 1 large and 3 smaller, allowing the animals to regurgitate the food, from the stomach to the mouth, in the form of small balls, and chew it. The ruminants include some of the most known pets: the cows, the buffaloes, the goats and the sheep.

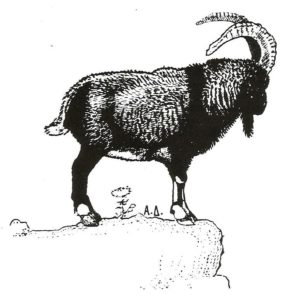

Wild Goat of Eremolilos [Ibex] (Capraaegagruspictus). Endemic subspecies, found only in Eremomilos (Antimilos) and related to Agrimi or Aigagro of Crete (C. a. Cretica). Both Greek subspecies resemble each other, but the subspecies of the Cyclades are characterized by a reddish-brown color, especially the female, and the black spots of the body (back, forefoot and shoulder, beard and upper tail). The Wild Goat of Eremomilos was known at the time of Erhard, who in the work of Faunader Cykladenattempts to differentiate this animal from Agrimi of Crete, mainly because of the deviation and the form of the horns (but also the shape of the male beard). However, the coloration of the animals is not, by itself, a reason for differentiation, since it can vary according to gender and age. Erhard had proposed the name Aegoceruspictusfor this animal.

Nowadays the Wild Goats of Eremomilos are protected, and at least in the immediate future they are not threatened with extinction, although the conditions on the island, with the lack of surface water, are not the most favorable. The greatest danger seems to come from the genetic mixing with (domesticated) goats, and doubts have indeed been expressed about genetic purity, even for the very identity of these animals. Horn divergence and coloration are direct indicators of the particularity of each specimen. The Forestry and the inhabitants of Milos have been making significant efforts for the protection of Wild Goats for years.

The Wild Goat is an ancestor of today’s domestic goat and looks much like it. Intermediate species have been and still are today widespread throughout the Mediterranean, especially in the Greek islands; but nowadays it has become evident that there is a great degree of genetic mixing of these animals, so much that they are no longer considered wildlife species. An exception is the Cri-Cri of Crete (Capraaegagruscretica). Some populations on some islands appear to have been imported from Crete and elsewhere (the species is also found in southwestern Asia Minor) already since the time of the ancient Greeks. The Wild Goats live in groups where the males make a strong presence during the mating season late in the autumn and winter. They feed on a wide variety of plants either by grazing or cutting leaves and stems from the trees, resting on the hind legs and standing up, like the goats. In Eremomilos there is currently a population of Wild Goats, which consists of 400–500 individuals. This population is considered to belong to the subspecies Capraaegagruspictus, which is not found anywhere else. Most of the individuals of this population, show more or less visible signs of hybridization with domestic goats, a problem that characterizes the Greek Wild Goat populations as a whole and, to limit it, all hybrids and domestic animals that live on Eremomilos should be distroyed. It should also be appropriate to protect the whole island by designating it as a national park and to keep the goat population at levels that do not reach the limits of artificial overpopulation due to complementary food supply (Sfoungaris 1990).

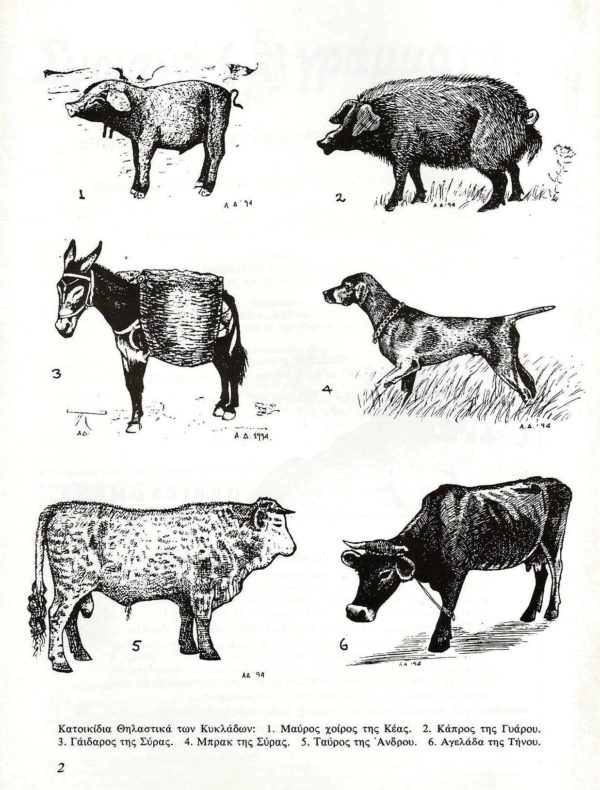

Pets and Domestic Animals

Apart from wildlife living in the Cyclades, there are domestic animals found on some islands descended from very old, often small, breeds. Today most of these breeds have already disappeared or tend to disappear, and their protection is required. These breeds are the result of centuries of adaptation to the arid, inhospitable environment of the islands, where these animals had to survive and produce for men, exploiting highly degraded food sources, or tolerate adverse environmental conditions, with the main problem being the lack of surface water. Companions of the islanders in long, hard periods, Cycladic domestic animals have so far arrived to be replaced by the wheel, improved breeds, and the intensification of agricultural production; this, even when the profession of animal farming is abandoned on islands like Syros. The brak (sic) of Syros, the pig of Kea, the donkey of Syros, and the cow of Tinos, as they were known in the daily talk of the islanders, will soon disappear if there are no breeding cores to reproduce them. To these breeds one can add animals which have been imported to the islands on a periodic basis, preserved for a period and then declined, such as the “heavy” Hungarian horses and the “camatera [burden]” buffalo (in Syros), even the South American Llamas (Gyaros). Cats, goats, pigs and rabbits are present in the wild on many inhabited and barren islands of the Cyclades (Gyaros, Gaidouronisi, Rinia etc), and often these populations are the result of old imports (in the case of cats and rabbits, these populations come from imports that were made centuries ago but are also reinforced by repeated “inflow of new blood”). In many areas, such as in Sa-Mihalis of Syros, as well as in entire islands such as Gyaros, the inhabitants abandoning their homes (gradually in the first case, suddenly in the second), released the animals, leaving them to their fate and so they created a new population in nature. Elsewhere, as in Gramvousa, the inhabitants systematically abandoned their animals when they grew old, not to kill them. Thus, many of these islands were named Gaidouronisia [Donkey Islands] for that reason (perhaps the information that the islanders killed or abandoned the old animals in certain places, such as Lazareta in Syros should be added here). Only few cows of the Tinos breed survive today, since it has been displaced by improved breeds, which are regularly bred throughout Greece. A particular breed, which seems to be a cross of Schwitz with the Russian cow, or the cow of Tinos, it resembles in some of the morphological characteristics the Indian Zebu. Despite the poor diet of these animals, their yield was very satisfactory, with milk production reaching 1,000 kg per year and a fat content of 5,20%. The height of the animals of the Tinos breed is 1,18–1,36 m and the weight is 325–340 kilos, while their color is blond, fiery or silver-blond. The bulls (bugades; bugas, bugadi, in the local idiom of Tinos and Syros) were raised for fattening. Several local cow breeds existed previously in the Sporades Islands—where few specimens are preserved today—but also in Gavdos. These animals were brownish or whitish, while the bulls were white with varying gray tones in the head and the front neck. Their horns were sickle-shaped and larger than those of the bulls that belonged to the Cyclades.

source: Syros Letters, Vol. 29, 1995

Translated by Constantine Hatziadoniu

Amphibians and Reptiles of Syros

3 August 2016

By Achilles Dimitropoulos

The Aegean space, and especially the Cyclades, has been a rich field of study for herpetologists, and Syros often hosted researchers interested in amphibians and reptiles. The geographical isolation of the islands, which led to the creation of characteristic subspecies, has attracted those scientists who were specialized in the study of problems in Systematics1. The Cycladic reptile fauna is rich and varied, including characteristic, unique subspecies, isolated on one or two islands, as well as two species unique in the world: Chalcides moseri and Elaphe rechingeri.

Asiatic species from Asia Minor arrived in the Cyclades in the past and today they meet in Mykonos and Delos (Agama stellio) or even in Milos (Vipera lebetina). On the contrary, species of the Balkan fauna while passed on an island, they were absent from its neighbors. Thus, Laftitis is a common snake in Mykonos, but has not been found in Syros.

Already classical and almost outdated, but always interesting, are the extensive publications by K. Buchholz, F. Werner and C. von Wettstein, who devoted much of their research work to the Cyclades; in these works there are repeated references to Syros. Among the modern researchers, R. Clark reports the presence of a spiked variety of common viper (Vipera ammodytes), which coexists in Syros with the common one that has the zigzag shape on the spine. This snake, which is relatively small, is very rare today and, as R. Clark himself told this author, it was caught very close to Ermoupolis.

The most systematic work on the reptiles and amphibians of Syros and the small uninhabited barren islands around it was made in 1980 by two distinguished researchers of the reptiles of Greece, Axel Beutler and Emil Frör and published in the Mitteilungen der Zoologischen Gesellschaft Braunau entitled “Die Amphibien und Reptilien der Nordkykladen”.

The scientists visited Syros on 3-4 / 10/1974 and 27 / 5-116 / 1977, and on these dates they made identifying visits to the barren islands of Didymus (Megalo Gaidouronisi), Mikro Gaidouronisi, Psathonisi, Schinonisi, Aspronisi and Stroggylo.

In Syros there is 1 species of amphibian and 11 species of reptiles: 1 turtle, 5 lizards and 5 snakes.

Near the inhabited areas, as well as in the few places where there are cisterns or springs, Prasinophrynos [Green toad]—which the people of Syros call, erroneously, a frog—is the only amphibian species on the island. We often see it after rain or as it stands watching for insects where light happens to fall in the summer nights. It breeds in cisterns and waterponds and often performs small, group movements to and from the areas where it is reproduced. During these journeys, many toads are killed in the streets by cars.

In the earlier literature, the common frog (Rana ridibunda) and the Mauremys caspica rivulata are also mentioned, species found in Andros, Tinos and Mykonos, but they seem to be extinct in Syros. Perhaps the drying of the swamps or other wetlands has contributed to their extinction.

In Syros, there are two species of slow worms, Cyrtodactylus kotschyi and Hemidactylus turcicus (Molyntiri), often found near at or in homes). Kridodaktylos is a very interesting species because it has a very large distribution in almost all Aegean islands , even in the small barren islands that are far from the shores. Its form varies from island to island, and so we have a large number of subspecies distributed in the Cyclades, Crete and the surrounding islands as well as the islands of the East Aegean.

Two species of diurnal lizards are found in Syros, the large Lacerta trilineata, known as the Colosauros and the much smaller Podarcis erhardii, which in the Cyclades is called Silivouti or Silivutaki and is found in large numbers near “hard walls” (old dry stone walls), old stone buildings, as well as curbs of country roads. Like Cytodactylus, it is also a diverse and very widespread species that counts many subspecies in the Cyclades. The males have dark patterns on a brown-green background, while the females are browner and streaky. The species in Syros and “Stapodia” (a barren island near Mykonos) belong to an intermediate species between the mykonensis subspecies and the naxensis subspecies. The Lacerta trilineata of Syros belongs to the same subspecies as the populations of Naxos, whereas Podarcis erhardii of Gyaros belongs to the same subspecies as the population of Mykonos; the species also exists in the small islands around Syros (Mikro and Megalo Gaidouronisi, Asprochori, Strongylo).

For the snakes of Syros and the surrounding islands there are old references, from Erhard to Wettstein, and nowadays R. Clark. In the literature, 5 species are mentioned, of which the most famous is the Elaphe situla (house snake), which in the old days people deliberately brought to their cellars to eat the mice. The house snake is, of course, the most beautiful and harmless snake in Europe. It has brownish red spots on the back, framed with black outline, while the body’s basic color can be whitish, yellow, creamy or grayish. It is often found in homes in the city and in the countryside, near stone walls, old stone buildings, and in fields.

The water snake, Natrix natrix, being adapted to the barren nature of Syros, is often far from water sources and feeds more on lizards and rodents than frogs and toads, which are its main food in wet areas. The species populations of Syros are an intermediate form between the black or spotted subspecies of Milos (N. schweizeri)—which extends its distribution to Sifnos, Paros, Antiparos, Despotiko and other islands of the Cyclades—and to the very widespread, striped subspecies of the Balkans and Turkey (N. n. persa).

In the very dry areas there is a strange snake that becomes active at dusk and in the night, the Telescopus fallax fallax (Aghiofido). This snake, which chases lizards and rodents like a cat, is grayish brown with dark brown or black spots on the back and an overwhelming sign, like a cross, on the nape. It is more common in the wilderness of Apano Meria. It has a mild poison, but its teeth are at the back of the mouth, and cannot be used when this snake bites a man. However, Aghiofido is usually very tame and almost never attempts to bite, even when we take it in our hands; that is why during a feast in Cephalonia, the faithful are able to catch and wrap in the arms and the shoulders such snakes.

The only dangerous snake on the island is the common Viper (Vipera ammodytes meridionalis), whose bite is painful but rarely fatal. Both the typical kind with the characteristic gray-black or brown zig-zag pattern on the back, and the rare dotted kind discovered by R. Clark coexist in the northern part of the island, in the Aetos area, and in Pagos, where this author witnessed a biting, as a result of which the patient needed to stay for several days in the hospital.

Viper snakes are found in rocky and bushy areas, but often visit places where there is water, both to drink and to hunt birds or rodents. They are not aggressive, and you have to almost step on them to bite. In the spring they are active during the day, and as they go through the summer, they acquire nocturnal habits.

The reptile fauna of Syros has many similarities to that of central Cyclades, while the one of Andros, Tinos and Mykonos is a separate unit with many common species. The differences in the reptile and amphibian faunae of the Northern Cyclades are small compared to those of the Western or Central Cyclades, but there is a wide variation among the species that are found in the Cyclades and those found in Evia and in the mainland. For most species, the stone walls (many of which are now abandoned) are a basic biotope, and there we find the largest numbers; there are fewer reptiles in the bushy areas and the cultivated fields, while only the Molyntiri lives in the cities. Toad, as well as species directly dependent on water such as Lacerta trilineata and the Nerofido, are at risk and probably some of their populations have already been lost when this article is published.

(1) Systematics: is the science that deals with the classification of different organisms. It is also known as Taxonomy.

source: Syros Letters Vol. 7, 1989

Translated by Constantine Hatziadoniu

Birds of prey on Syros, now and then

3 August 2016

By Achilles Dimitropoulos

The Cyclades Were, and still are, the main passage in the migration of birds from and to Africa. Among these birds there always were some rather rare birds of prey as the Sea Eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla), the Imperial Eagle (Aquila heliacal), the Booted Eagle (Hieraaetus pennatus) and various species of falcons as well as all the Harrier (Circus) species, which live in Europe. Even today the Harriers and the Red-footed Falcons (Falco vespertinus) are frequent visitors of Syros, especially in autumn. However, there were few birds of prey that stayed and nested on the Aegean islands, apart from the Peregrine Falcons (Falco peregrinus), the Eleonora’s Falcons (Falco eleonorae) and the Kestrels (Falco tinnunculus) which still nest on Syros, in much reduced populations than those that older hunters tell us or that we are informed from the bibliography.

Searching this particular bibliography, we saw that this was not always the situation. There were big birds of prey on Syros, at least till the middle of the last century. This evidence is proof that there existed on the island the food and environmental conditions which were perfectly appropriate for the permanent presence of these vulnerable birds. Certainly, a great part of the island was rutty and remote, especially the north and south-west part. The existence of natural prey secured the survival of the hunting species but also, occasionally, especially in the winter, they fed on carcasses. These species are the Sea Eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla),and the Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos), the greatest and most impressive of all the eagles of Europe.

It is almost certain that there was some movement of Sea Eagles (Haliaeetus albicilla),above the Cyclades and the islands of East Aegean; birds of this kind have been killed at times in Andros, Tinos, Lesbos, Chios, Samos (where the species probably nested at the coastal forests which were since burnt), Ikaria, Kos, Patmos and Symi. According to I. Choremis, this species nested on Chios till 1960.

Today, there are one or two couples of Sea Eagles (Haliaeetus albicilla)living in all of the Greek territory. The species is under immediate danger of extinction in Europe as well as in the rest of the world. There exist indications that Sea Eagles (Haliaeetus albicilla)nested on Gyaros till the II World War; there are many relevant testimonies of fishermen who saw them feeding on dead seals and dolphins which were washed out on the beach, while the last Sea Eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla)was killed on Gyaros and was stuffed and mounted in Syros by the taxidermist Panagopoulos.

Young Sea Eagles (Haliaeetus albicilla) were observed on Syros on 1981, 1983 and 1985. These birds were traveling and certainly came from far away. It is certain that this species does not exist anymore in the Aegean and it is just passing by the area during migration. The birds that are observed in the Cyclades most probably come from Scandinavia or Russia.

Already, since the middle of the previous century, the populations of Sea Eagles (Haliaeetus albicilla) were reduced significantly and the distribution of the species shrank. The destruction of wetlands and of forests where they nested, the illegal and uncontrolled hunting, the use of poisoned baits for the control of the so called “pest species”, as well as the wide use of pesticides which caused infertility in birds of prey, were decisive factors for the gradual decline of the species, both in Europe and in Asia. In Greece there are no more than one or two couples that reproduce. In the Sporades, the Cyclades and East Aegean, the older fishermen still remember the Sea Eagles (Haliaeetus albicilla) which nested on rocky beaches and uninhabited islands, as is that one south of Chios, where the last bird was seen in 1967.

Testimonies of travelers and explorers prove, often through detailed reports, the existence of Golden Eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) in the Cyclades, especially in Syros but also in Mykonos. Although the Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos)is not as rare as the Sea Eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla) (they exist in the mainland of Greece and Crete) they still are birds of prey who cover great distances for hunting, daily. Thus, its survival on the Cyclades depends directly on the existence of food and most of all on the preservation of the biological balance of expanded areas, free from human intervention. We all know how difficult is to preserve these conditions on our islands when they have undergone touristic and other kinds of developmental activities. A single pair of Golden Eagles was breeding in Syros from 1988 to 2009.

In the classic study of Erhard on the birds of the Cyclades there are various reported testimonies for the existence of Sea Eagles(Haliaeetus albicilla) and the Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos)in Syros. According to this distinguished scientist, an impressive adult eagle who for a long time had been observed living free on the island, was captured and was transferred to the Zoological Garden of Trieste on the care of the ambassador v. Hahn. There, the eagle was deemed a rare acquisition due to “the intelligence she had shown during her taming”. In this same text, Erhard reports how a couple of Golden Eagles(Aquila chrysaetos)has remained on Mykonos, how their nest is situated near the beach, how they fed on stray dogs and cats. This report leads to the conclusion that already at that time, the natural prey of eagles was scarce. An old and possibly sick or exhausted individual, which, from the description, appears to be (Eastern race of) Imperial Eagle (Aquila heliaca)—today, a species on the border of extinction—was found during the migration on the island, and there she died.Erhard also gives information about the birds of Syros in the scientific journal Naumannia(1856 and 1858), among which reports that in mid-August 1857 two young falcons that had taken from a nest, were brought to him. According his description they should be Eleonora’s Falcons (Falco eleonorae) a species of falcon which still nests on the island. This same period, the explorer discovered a large colony of vultures in Mykonos. Today, there are a few vultures only in Naxos; the nearest to the Cyclades colonies are to be found in Evia.

When the winter was unusually severe, there arrived in Syros—always according to Erhard—Great Bustards, which the locals called “Wild Turkey” (Otis tarda).Today the Great Bustards,large birds, the size of turkeys, are extinct in Greece and they are an endangered species all over the world. Moreover, Erhard made the unique observation of Common Bulbul (Pycnonotus barbatus)in Greek territory. The Common Bulbul (Pycnonotus barbatus)is a dark songbird the size of a Song Thrush (Turdus philomelos) that is encountered in the Middle East and very seldom west of Turkey. The observation of Erhard is of great importance as it does not concern a single individual but a couple which was brought to him, alive from Santorini.

Scientific name of the birds from here

Translated by Aliki Tsoukala / Edited by Constantine Hatziadoniu

The fauna of Syros today

10 October 2016

by Achilleas Dimitropoulos

SPECIES OF BIRDS OBSERVED NESTING IN SYROS DURING THE PERIOD FROM SPRING 2009 TO SPRING 2016

This list does not include migratory species that pass through Syros and are observed during migration but do not nest here. Species that are winter or sporadic visitors are also not included, as well as species reported in the literature before 2000; these reports will be the subject of other publications in the future. The purpose of this publication is to learn about the current situation on Syros.

| Phalacrocoracidae family |

| Phalacrocorax aristotelis (Linnaeus, 1761) |

| Accipitridae family |

| Buteo buteo (Linnaeus, 1758) |

| Aquila chrysaetos (Linnaeus, 1758) |

| Falconidae family |

| Falco tinnunculus (Linnaeus, 1758) |

| Falco peregrinus (Tunstall, 1771) |

| Phasianidae family |

| Coturnix coturnix (Linnaeus, 1758) |

| Alectoris chukar (J. E. Gray, 1830) |

| Laridae family |

| Larus cachinnans (Pallas, 1811) |

| Columbidae family |

| Columba livia (J. F. Gmelin, 1789) |

| Steptopelia decaocto (Frivaldzsky, 1838) |

| Tytonidae family |

| Tyto alba (Scopoli, 1769) |

| Strigidae family |

| Athene noctua Scopoli |

| Otus scops (Linnaeus, 1758) |

| Asio otus (Linnaeus, 1758) |

| Caprimulgidae family |

| Caprimulgus europaeus (Linnaeus, 1758) |

| Apodidae family |

| Apus apus (Linnaeus, 1758) |

| Apus pallidus (Shelley, 1870) |

| Alaudidae family |

| Galerida cristata (C. L. Brehm, 1841) |

| Turdidae family |

| Oenanthe hispanica (Linnaeus, 1758) |

| Monticola solitarius (Linnaeus, 1758) |

| Turdus merula (Linnaeus, 1758) |

| Sylviidae family |

| Sylvia melanocephala (J. F. Gmelin, 1789) |

| Corvidae family |

| Corvus corone (Linnaeus, 1758) |

| Corvus corax(Linnaeus, 1758) |

| Passeridae family |

| Passer domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758) |

| Passer hispaniolensis (Temminck, 1820) |

| Fringillidae family |

| Carduelis chloris (Linnaeus, 1758) |

| Carduelis carduelis (Linnaeus, 1758) |

| Carduelis cannabina (Linnaeus, 1758) |

| Emberizidae family |

| Emberiza calandra (Linnaeus, 1758) |

AMPHIBIANS & REPTILES OBSERVED IN SYROS

| AMPHIBIANS |

| Bufonidae family |

| Pseudepidalea viridis (Laurenti, 1768) |

| Ranidae family |

| Pelophylax kurtmuelleri (Gayda, 1940) |

| REPTILES / FRESHWATER TURTLES |

| Emydidae family |

| Mauremys rivulata (Valenciennes, 1833) |

| LIZARDS |

| Gekkonidae family |

| Cyrtopodion kotschyi (Steindachner, 1870) |

| Hemidactylus turcicus (Linnaeus, 1758) |

| Lacertidae family |

| Lacerta trilineata (Bedriaga, 1886) |

| Podarcis erhardii (Bedriaga, 1882) |

| Scincidae family |

| Ablepharus kitaibelii (Bibron & Bory, 1833) |

| Chalcides ocellatus (Forsskal, 1775) |

| SNAKES |

| Colubridae family |

| Dolichophis caspius (Gmelin, 1789) |

| Natrix natrix (Linnaeus, 1758) |

| Telescopus fallax (Fleischmann, 1831) |

| Zamenis situlus (Linnaeus, 1758) |

| Viperidae family |

| Vipera ammodytes (Linnaeus, 1758) |

TERRESTRIAL MAMMALS OBSERVED IN SYROS

| Erinaceidae family |

| Erinaceus concolor (Martin, 1838) |

| Muridae family |

| Rattus rattus (Linnaeus, 1758) |

| Rattus norvegicus (Berkenhout, 1769) |

| Mus domesticus (Rutty, 1772) |

| Mustelidae family |

| Martes foina (Erxleben, 1777) |

MARINE MAMMALS OBSERVED IN THE WATERS AROUND SYROS

| Phocidae family |

| Monachus monachus (Hermann, 1779) |

| ΚΗΤΩΔΗ |

| Balaenopteridae family |

| Balaenoptera acutorostrata Lacépède, 1804 |

| Balaenoptera physalus (Linnaeus, 1758) |

| Physeteridae family |

| Physeter macrocephalus (Linnaeus, 1758) |

| Delphinidae family |

| Delphinus delphis (Linnaeus, 1758) |

| Stenella caeruloalba (Meyen, 1833) |

| Tursiops truncatus (Montagu, 1821) |

| Grampus griseus (G. Cuvier, 1812) |

| Pseudorca crassidens (Owen, 1864) |

Translated by Marina Konstantopoulou

photo: Chara Pelekanou

Useful links:

Area folder – GR4220032 Βόρεια Σύρος και νησίδες